Who’s in Charge?

A new model for understanding family business ownership

By Patricia M. Angus – Originally published in Trusts & Estates, March 2019

Family businesses are complex in many ways. They’re inevitably a mix of entrepreneurial spirit, family connections, business challenges and evolutionary processes spanning multiple dimensions all at once. Any lawyer, accountant, investment advisor or, most importantly, family business consultant, working with a family business needs a variety of frameworks, tools and perspectives from many disciplines to provide the best advice to a family business. Academics and practitioners have developed some useful frameworks to aid this process, but there still are too few. One area especially in need of attention relates to family business ownership. Too often, advisors make assumptions about key questions—who owns the business, how it’s held and for what purpose—that limit their ability to fully understand and provide the best advice to a family business. Here’s a new way of looking at ownership to assist advisors working with family businesses so that they can more effectively assess and advise their clients.

The Three-Circle Model

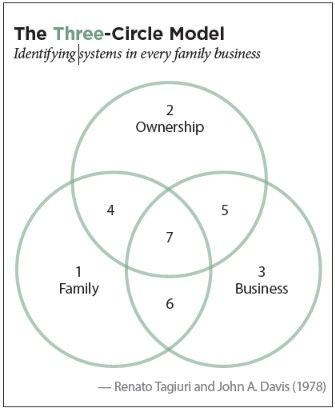

In the field of family business consulting, there are few, if any, heuristic models used as universally as the “Three- Circle Model.” Created in 1978 by Renato Tagiuri and John A. Davis, the model is a simple Venn diagram illustrating the three systems identified in every family business: family, ownership and business management.1 Rooted in an organizational development framework, it’s based on the assumption that each group functions as a system with its own culture, individual motivations and internal relationships. It aims to create clarity by providing a place, and only one place, for each individual in all of the three systems. (See “The Three-Circle Model,” p. 49.) For example, a family member CEO who doesn’t own any shares in the business is placed in Sector 6, while a family member who neither owns shares nor works in the business belongs in Sector 1. With these placements, one can objectively identify what each individual might want, and not want, from the family business. And, how their actions can be understood in that context. A family member—theoretically at least—wants love and harmony; an owner seeks growth and dividends; a manager seeks profits and income from salary and bonus. The Three-Circle Model can be used to help educate and diffuse tensions among members of a business-owning family who are at odds. For example, reframing a son’s desire for a higher salary can be more understandable when a father understands that any non-family member employee would want the same. A family member’s pleas to “leave business at the office” can be more understandable when it’s made clear—visually—that the role of a family member is just that—to preserve harmony in the family. Empathy can increase with this increased understanding.

The Three-Circle Model is also helpful to shed light on the common, and complicated, position in which many members of a business-owning family find them- selves. That is, when they hold multiple roles that are —by definition—in conflict with each other. A family member CEO who owns all, or part, of the business is in an especially delicate position. There’s a natural tension among running the business, maintaining the family and realizing an owner’s legitimate expectations from the business. Indeed, one might argue that many family businesses often fail when these tensions aren’t resolved or at least managed. And, in this case, failure isn’t just the casualty of a business that dies, but also fractured family relationships, hardship for employees and disruption in the community.

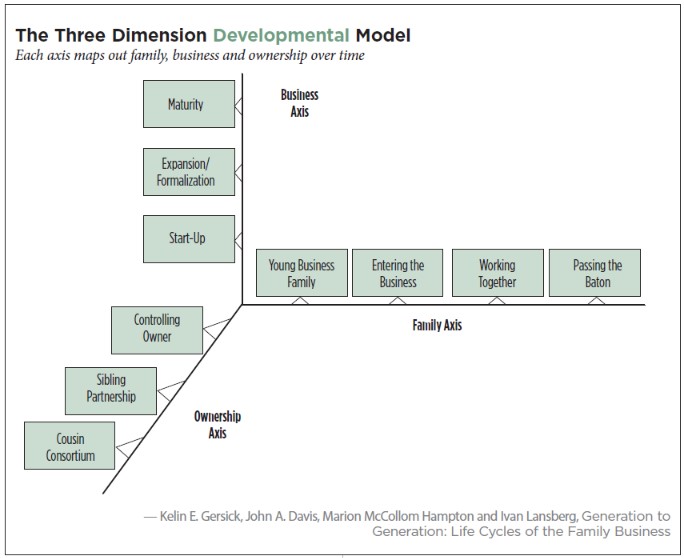

A second classic model is found in the seminal “Three Dimension Developmental Model,”2 p. 50, in which each of three axes maps out family, business and ownership over time. The ownership axis evolves from Controlling Owner to Sibling Partnership to Cousin Consortium. Again, the assumption is that ownership is held by individuals.

Challenges to the Models

Like any good model, the Three-Circle Model and the Three Dimension Developmental Model have their limits. First is the assumption that each group functions as a system unto itself. For example, it would be hard to say that a system comprising all shareholders of a family-controlled public company functions similarly to a group of shareholders who own a privately held family business. Second, there are obviously multiple other systems at play in any family business, including vendors, customers and the community. Where do they belong?3 Where does the legal system fit? Culture? Third, there are evolutionary changes afoot in each of the groups that put pressure on their definitions and boundaries. For example, the very notion of “family” is changing around the world, which triggers questions, including: Where do non-married partners belong? What about divorced spouses who are still considered part of the family? Business practices are changing fast too. Where does an independent contractor who isn’t an employee belong? Most importantly, the major flaw in the Three Dimension Developmental Model is the implicit assumption that ownership is held by individuals.

Using these models, it’s all too easy for family business consultants to assume that ownership of a family business is always held by individuals who are acting for themselves. A potentially fatal flaw. But, let’s not throw out the baby with the bathwater. First, let’s admit that the major differentiating factor between family and non-family businesses is neither the family nor the business. It’s ownership. And, this is the least understood area, a reality that’s made even worse by the existing models.

Tax, Trust, Legacy Planning

In addition to limits of these family business models, the increasing sophistication of tax, trust and estate planning has exacerbated the confusion around ownership. It doesn’t take long for an owner of a business to realize (with the lawyer’s assistance) the benefit of placing company shares into a trust or other holding structure (such as a limited liability company)—to minimize taxes, protect assets and/or provide for transfer across generations. Today, any business owner who enters a lawyer’s (or wealth advisor’s) office with any of these goals in mind is likely to leave with one or more trusts into which shares of the business will be transferred. Individual ownership is going the way of the horse and buggy.

For these reasons, a simple heuristic device is needed to quickly assess the nature of the overall ownership of a family business. The key question is whether the business is held entirely by individuals, by holding structures, such as trusts, or a combination of both. In the family business context, these distinctions make all the difference.

New Ownership Categories

Ownership of family businesses falls into one of three distinct categories: direct, indirect and hybrid. These apply whether the business is privately or publicly owned.

All direct owners. In this type, direct family businesses are owned solely and directly by individuals who hold shares in their own names—each individual has full, unfettered control of her shares. Most often, the shares are held by family members, but there may be other individual shareholders as well. Most found- er-controlled family businesses fit into this category, often with the founder owning 100 percent of the shares. Over time, the founder might give or sell some shares to other family members or investors. In many countries other than the United States, this is the norm for family business ownership. The benefit of a direct owner business is that each shareholder has her own voice, with each individual’s rights and responsibilities held in a personal capacity. In shareholders’ meetings, each shareholder represents herself, and buy-sell contracts are negotiated between individuals.

In a family business context, this category can make it especially difficult for family members to distinguish roles and motivations. Interactions among owners can mix personal and business issues. When is someone speaking as a father, when as a controlling shareholder? When as a sister, and when as a co-owner?

In this case, family members would be well advised to learn about how to distinguish between their desires for the family from those of the business. Financial success for the business might require decisions that are uncomfortable for the family. For example, a sale of the business might feel like the death of a family member. It’s essential to be able to distinguish fact from feeling.

All indirect owners. This category consists of businesses that are owned entirely by trusts and other holding structures. The business is owned by one or more trusts that are the “legal” owners, while individual family members, and potentially others, are “beneficial” owners. In the past, a family business often didn’t fit in this category until after the demise of the first generation, when the shares of the business passed into trust from the founder’s estate. But, today, in the United States and increasingly in other parts of the world, this transfer can happen even before the company is established. In some cases, there’s a single trust, with one or more trustees who is/are the legal owner(s) of the business. For others, individual family members create trusts to own their respective shares, and/or voting trusts may be in place to consolidate control. In each case, the legal owners are trustees acting on behalf of others (current and future beneficiaries). This setup creates layers of fiduciary responsibilities, sometimes in conflict with each other. A buy-sell agreement must be negotiated among the trustees of the various trusts, who may or may not be family members and by definition are one step removed from those who benefit from the company. Principal/agent issues arise within the ownership group. The trustees—as owners—must keep in mind their fiduciary responsibilities, especially when they might have a beneficial interest as well. Individual direct owners don’t have such limitations, and it’s all too easy to forget the difference.

In this case, family members, especially business founders, may not know, understand and/or want to accept the legal reality of how the business is actually owned. De facto authority may be in conflict with the de jure reality. Trustees who are family members may find it especially difficult to distinguish between their positions as legal owners of the business with their fiduciary responsibilities to trust beneficiaries. Family members may not understand that their voices with respect to the future of the business may be limited by the legal reality of their positions as beneficiaries rather than direct owners. And, well-meaning family business consultants may put a lot of energy into educating family members as to their opportunities and responsibilities as owners, only to find out that, in fact, those family members have no legal authority to act on their wishes. A harsh reality.

Hybrid. The third category is where more family businesses will find themselves at one point or another. The family business is owned partly by individual family member(s) and partly by trustees. This setup combines the clarity of direct ownership with the complexity of fiduciary responsibilities, often including the very same family members in each capacity. Principal/agent dis- tinctions can get quite confusing in this category. For these businesses, a buy-sell agreement must be negotiated and agreed to by each party with clarity as to her role and authority. A family member trustee who also owns shares in her individual name is actually two separate parties to the agreement. Family members who are speaking with each other as owners must remember to include trustees who are owners and legally have a right to be in the conversation.

Applying the New Ownership Model

This New Ownership Model can help family business consultants and others to analyze and work with a family business in a more effective way. (See “The New Ownership Model,” p. 51.) Certainly, the New Ownership Model has its limitations and flaws, as any attempt to simplify such a complex matter would. Nonetheless, it’s hoped that family business consultants, and other advisors to family businesses, will consider whether and how it might help for them to apply the categories outlined above to a specific client situation. This strategy might go a long way to helping families better understand their reality and make the best of it, for themselves and all stakeholders involved.

Endnotes

- Renato Tagiuri and John Davis, “Bivalent Attributes of the Family Firm,” Family Business Review (1996).

- Kelin E. Gersick, John A. Davis, Marion McCollom Hampton and Ivan Lansberg, Generation to Generation: Life Cycles of the Family Business (Harvard Business School Press 1997).

- See Bonnie Brown Hartley and Gwendolyn Grittith Lieuallen, Family Wealth Transition Planning (Bloomberg Press 2009).