The Family Governance Pyramid: Enhancing and Guiding Your Family Philanthropy

By Patricia M. Angus – Originally published in NCFP’s Passages July 2021

OVERVIEW

Family philanthropy is a very important expression of a family’s commitment to society. It is a high calling for a family that wishes to have an impact greater than their individual efforts alone could accomplish. A private family enters the public realm to visibly support the social contract—the combination of efforts by government, business, and eleemosynary organizations that hold society together. And, just as government and business require sound governance to do their work well, so too do families—and their philanthropy— owe it to themselves and society to be governed well. The Family Governance Pyramid provides a model and framework for philanthropic families that is even more relevant and necessary today than when it was first introduced nearly two decades ago. This article provides some perspective on why, and how, families can apply this model to their family and philanthropy, for the good of all.

INTRODUCTION

Family Philanthropy’s Role in Society

More than 2,000 years ago, Greek philosopher Aristotle noted that families are the fundamental unit of society. Little did he know how important families would become in the ensuing millennia as they increased their contributions to society through family philanthropy. Some countries, most notably the United States and United Kingdom, built their social contracts around an assumption that private individuals would contribute to others in need. Based on social and cultural norms, this assumption is embedded in legal and tax systems that provide benefits and structured options for those who make charitable contributions. The impact of private philanthropy is a significant part of the economy, with total US giving exceeding $400 billion in 2020. The non-quantifiable impact is even more profound. Countries around the world have evolved to incorporate the UK/US model to find ways to promote and support private philanthropy. As philanthropy has become vital to society, families have become the major funders, conveners, and drivers behind this global phenomenon.

Despite this reality, family philanthropy is often portrayed, and occasionally practiced, as though it were solely accountable to the family alone. Families are often encouraged to engage in philanthropy to “keep the family together.” They are advised to engage younger family members so they can gain valuable experience where the “stakes are low;” with the hope that they’ll later transfer these skills to other “more important” areas such as business or family investments. For many, the preservation of the family and its wealth appears to be the one and only goal; philanthropy is a means to that end. In this environment, effective governance is overlooked at best, and undermined at worst.

These messages are not only misguided but in fact harmful—not only to the family members who receive them but more importantly to the society that relies upon the support of family philanthropy to fill needs that are not met by government or business. One must ask: Doesn’t the fundamental unit of society, upon which so much of society’s welfare depends, require governance? Doesn’t it make sense for the family to focus on its own governance, and the governance of its philanthropy, so that it can rise to its highest calling? Wouldn’t that be best for the family and for society?

The answer to each these questions is a resounding “yes.” Indeed, the answers are so compelling that it leads one to paraphrase US President John F. Kennedy’s famous words—ask not what philanthropic families need from society but what society needs from philanthropic families. In these times of increasing inequality and social upheaval it is more important than ever for philanthropic families to rise to the needs of society as best they can. This article covers these issues, and more, through an exploration of family governance as it applies to family philanthropy. Each of the following sections may be read in isolation or in sequence:

- The purpose and power of family governance

- Effective family governance: The Family Governance Pyramid

- Applying the Family Governance Pyramid to your family philanthropy

The article ends with closing thoughts to foster further reflection.

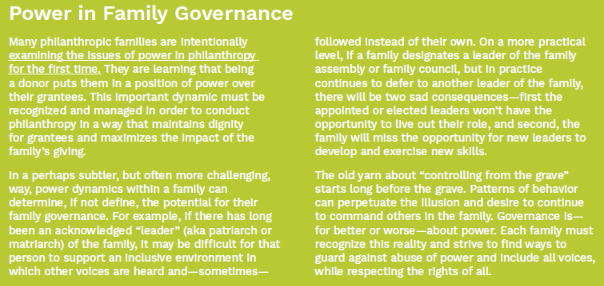

THE PURPOSE AND POWER OF FAMILY GOVERNANCE

Academics and practitioners from various disciplines have been developing the theory and practice of family governance for several decades. To date, the impact of family governance on family philanthropy has not been studied in full. But the evidence of its impact on family business provides a good guide. If we apply these learnings to family philanthropy we can extrapolate that a family that focuses on its governance through family governance mechanisms will also end up with more effective family philanthropy. The primary motivation for the development of family governance has been to create a way to preserve and enhance a family’s wealth and ensure that a family business survives across generations. To this end, families have benefitted from creating some structure and form to govern their joint endeavors. It is now commonplace for major family-owned businesses to have governance protocols, charters, and forums for exchange to manage the relationship between a family and the business it owns. At the same time, this development has a dark underbelly; family governance is often used to isolate and insulate wealthy families from society rather than integrate them into it. Again, this leads to a more fundamental question: can family governance be used for the good of all? One can certainly hope so.

The Essential Definition of Family Governance.

Family governance concerns itself primarily with the management of complex structures, legal and emotional relationships among family members, and how they are aligned with the direction that the family seeks to pursue over time. A basic dictionary definition defines governance as “the act, process or power of governing; the state of being governed” while to govern means “To control the actions or behavior of; guide; direct… to make and administer public policy for … exercise sovereign authority in … ”. The word itself finds its origins in the ancient Latin gubernare: “to steer (a vessel), to direct, rule, govern.” This provides a powerful metaphor for thinking about governance—guiding and steering with movement toward something. Put simply…

Family governance is the way in which a family guides and steers its collective endeavors toward a common goal.

It is essential to start with this simple definition and not be confused by the many ways that family governance has been used in years past. For example, the most commonly used definition—collective decision making—is insufficient because it lacks a sense of movement and purpose. Similarly, using the term to merely describe the mechanisms and entities without acknowledging their purpose doesn’t do justice to the concept. This confusion is exacerbated by the assault on governance itself in this era.

Governance Under Threat

Any consideration of family governance today must be placed in the context of national and global trends. Worldwide, governance has been the focal point of the most important and challenging developments within and among nations in the past decade or so. Indeed, the World Economic Forum identified inadequate governance as one of the greatest risks to the world in 2017. As 2021 began, the United States, long one of the most stable democracies, found itself struggling with the peaceful transfer of power. Protestors literally breached the seat of government, putting the lives of the nation’s top elected officials at risk. At that moment, political battles were not the issue. Rather, the very concept of governing itself was at risk. Globally, the non-governmental multi-national organizations created after World War II to prevent further wars and promote prosperity are under siege. Indeed, the world is struggling to define how it will be governed. All the while, the rising generation, known as “iGen,” have less interest in government and more distrust in institutions than prior generations. In this context, it is more difficult yet more imperative than ever that families to consider what governance means and how to effect good governance.

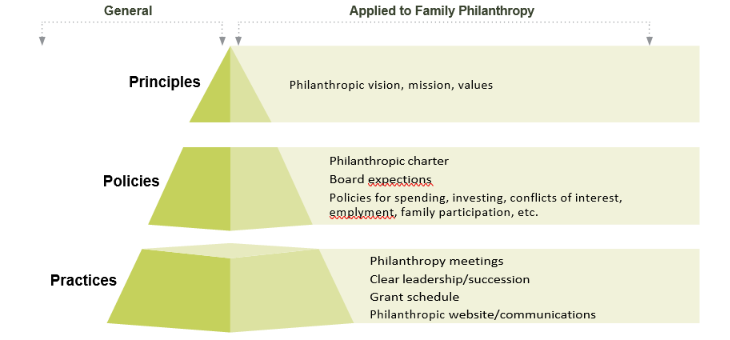

EFFECTIVE FAMILY GOVERNANCE: THE FAMILY GOVERNANCE PYRAMID

There is a hidden architecture behind society’s laws that—once revealed—provides the best way to envision governance in all its forms. At the highest level are the accepted principles of the community that come from sources deep in collective human history. As the late author and linguist William Safire wrote, “At the beginning was the principle: The Latin principium meant ‘source, origin, beginning.’ That came to mean a primary truth that formed the basis for other beliefs and then to mean a rule for ethical conduct.”

In governance, the principle is the starting point. As the founders of the United States stated in the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident …” Principles are the sine qua non of governance. They are more elemental and enduring than values, despite the way in which these terms are often used interchangeably. Again, William Safire has succinctly drawn the distinction: “values are neither standards of intrinsic worth nor eternal verities. They are relative, not universal …” “Values can change but principles cannot.” In science, the principle of gravity is one that cannot be broken.

A principle is a universal rule of thumb that answers the question of “why,” but principles alone are not enough. Legislators must translate principles into general policies. In the legal system these policies are then translated and implemented through laws and regulations. There is a hierarchy in these concepts, and an elegance in their simplicity. This framework is directly transferrable to family governance.

The Starting Point: Principles

To create an enduring family governance system, a family must work together to articulate their guiding principles. Since the family is not creating an actual legal system, there is some leeway in what can be included in this process and creativity can be applied in the articulation. A family must discover its own vision, values, and goals. Families should consider:

What are our shared beliefs? What distinguishes us from other families?

Do we have a common vision?

What are our guiding principles?

There are many ways to identify and articulate principles. As a starting point, the family might draw from its own religious, spiritual, or civic sense of the enduring principles that it aspires to follow. One common example is the “Golden Rule”—that is, do unto others as you’d wish to be done to you. Another principle might be that all people are created equally, or that all people should be treated fairly. A family might start with one of these principles and translate them into their own terms. It can then have the basis for developing a mission statement, or vision statement, or a list of shared values. Family members cannot assume that everyone will agree to each value or aspiration; rather they must respect the differences among themselves while focusing on the overlapping principles that hold them together. One way that principles can be found is through an organic process that is both aspirational (“How do we wish the family to be seen?”) and practical (“What is an example of our family’s uniqueness?”). See page 10 for some questions to help you with this process.

Relationship to the Social Contract

When determining the family’s principles, a family today must widen the lens to consider its role in the social contract—the combination of efforts by government, business, and eleemosynary organizations that hold society together. The family might consider starting with: What does the world need from us? It requires a humble perspective to start with that question, and in these trying times the answers are not easy. And yet the questions must be asked. What are the most pressing needs of the society? How might we, as a family, meet them? These questions in turn can raise profound inquiries into shared purpose and meaning that will lead to a principles-focused discussion.

Defining “Family”

The past few decades have put the definition of “family” under the microscope while the range of family configurations has evolved. In the United States, after years of battles, the Supreme Court declared that marriage will no longer be considered just between a man and a woman. Other countries have taken similar stances. In family governance, the definition of family has long been broader than a group of persons related solely by blood or marriage. It includes other important members who are joined to the family by an strong relationships with one or more members (see NCFP’s Passages Issue Brief, Families in Flux for an additional discussion). Each family must determine how its own family will be defined, and for different purposes. Perhaps a broad definition of family is used for a holiday gathering while a more restrictive definition is appropriate for ownership of a family business.

Setting Parameters: Policies

Families must establish ground rules for interactions about joint matters. While some families find it useful to establish a family constitution, others find that guidelines for family meetings are all that is needed. Policies should be written or, if not, must be simple enough that all family members can remember and agree to them.

The Allen family spent several years working on how to implement their principles. For their family, the Golden Rule was so important that they set a policy concerning treatment of employees in their family foundation. A living wage was a given and their giving was designed to ensure that grantees would receive the same level of respect that they that they would want to receive if their positions were reversed.

Governing Day to Day: Practices

The family must live its governance system in its day-to-day interactions. The family will have a variety of practices that they need to cover, in line with their principles and policies. Here, alignment is key.

The Allen family made sure that their policies were followed on a daily basis. They instituted feedback sessions with grantees and managers were provided with ongoing training on diversity, equity, and inclusion to ensure respectful behavior across all foundation operations.

Effective Meetings

One of the most important practices for any family is to have family meetings on a regular basis. This is where family relationships are built, education is offered, and strategic decisions can be discussed.

Families are accustomed to functioning informally, and norms of behavior and communication styles develop over time. This may work for casual gatherings, but it doesn’t work for families who are in philanthropy or other more complex endeavors together. Families must develop and follow an agreed upon system for calling meetings, creating agendas, and managing the meeting itself. Ground rules go a long way to minimizing family tensions and improving decision making. The most important thing is for the family to choose an agreed- upon meeting format so that everyone knows how the process will run.

A traditional—but not the only—option to consider is Robert’s Rules of Order. The impetus for this classic will likely sound familiar to many families who’ve endured informal meetings. According to legend, the original author, Henry M. Robert (1837–1923) found himself “[w]ithout warning … asked to preside over a meeting said to have related to the defence of the city in the event of Confederate attack from the sea and to have lasted for fourteen hours—and [he] did not know how.” After this experience he vowed to “never attend another meeting until I knew something of … parliamentary law.” A newer popular alternative is Martha’s Rules, which allows for more rapid decision making and ways to express partial agreement. Regardless of the system chosen, in family philanthropy it’s especially important for everyone to know the rules, for the rules to be applied consistently, and for family member’s opinions to be respected even if (and when) decisions go against one’s desires.

Quick Tip

See NCFP’s Family Meetings and Retreats Content Collection for examples of sample meeting ground rules and other guidance on holding effective and productive meetings.

Key Terms in Family Governance:

Family Council: Elected or appointed group of family members. Leads family governance and serves as conduit between Family Assembly and business, foundation and other formal family owned or funded entities.

Family Assembly: Largest group of family members who meet to build relationships, receive communications about family matters, and may have authority to elect or appoint Family Council.

Family Constitution: Document that defines family principles, sets out key policies, and outlines operational structure and accountability across family governance entities.

Social Contract: Organization of society, based on Western philosophical tradition, with goal of balancing freedom with security through government, business, and charitable organizations.

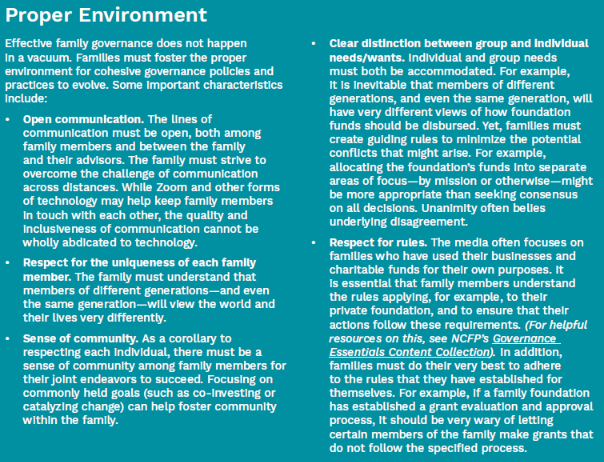

Ensuring Effective Family Governance

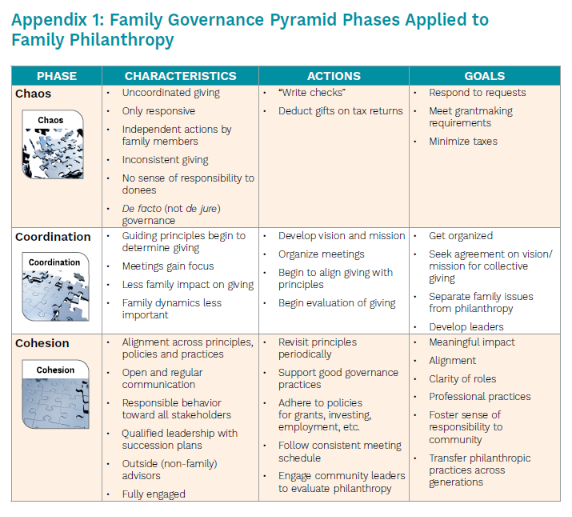

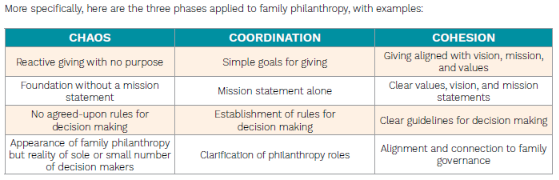

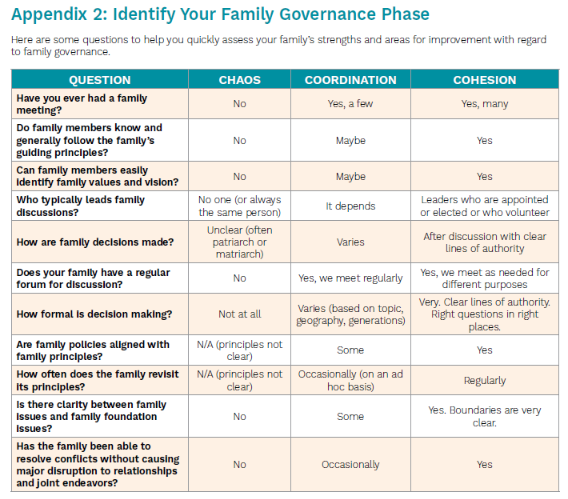

There are three basic phases in the development of a family governance system: chaos, coordination, and cohesion. If you are reading this paper, odds are that you are either looking to advance rapidly from “Chaos” to “Coordination,” or you are looking for necessary tips and skills for advancing from “Coordination” to “Cohesion.” To determine where you fit in this framework, please see appendices 1 and 2.

Phase One: Chaos. The first family governance phase is “chaos.” In this stage, family members may be living fulfilling lives and engaging in joint activities, but likely have no organizational structure, and have not yet articulated their guiding principles, much less developed aligned policies and practices.

The Lawler family has a major retail clothing chain and a diverse investment portfolio, and is quite generous in its charitable giving. The oldest generation is approaching 90, their children are in their late 50’s and the third generation are now graduating from college. They gather for major holidays and genuinely enjoy their time together. Some family members are working in the business, others are more interested in philanthropy. But they’ve never had a family meeting. They don’t know the terms of the oldest generation’s estate plans, and they have yet to discuss their common principles. Unbeknownst to the Lawlers, they are in the Chaos phase. In this phase, stability usually depends more on the underlying dynamics and relationships of family members than anything else.

Signs that your family might be in “Chaos”

- You’ve never had a family meeting.

- One person controls family decisions and direction around wealth, business, philanthropy.

- Things are (too) quiet.

- You don’t have advisors; if you do, they don’t work together.

- If you have had one or more family meetings, they’ve been focused on “technical” issues (finances, business reports, presentations) and are not engaging for family members.

- There seems to be no way out for insiders and/or no way in for outsiders.

- The stated values of individual family members are wide apart and there has been no attempt to find common ground.

- There may be an overemphasis on prior generation’s accomplishments, values, and vision which overshadows the sense of agency by younger family members.

- There is no process for family member’s voices to be heard about decisions that impact their lives.

Phase Two: Coordination. A family seeking to move its governance along will have to take steps to get to the next phase, coordination. A core group of the family will need to recognize that a transition is necessary and that it would be better to prepare before a crisis forces a change. A family member or small group of family leaders will have to take initiative to create a formal way of working together. This catalyzing person or group will need to initiate a family meeting or a series of meetings and start work on developing governing principles and policies. Existing advisors should be brought together, and new advisors found as needed. The advisors must understand that working collaboratively is in the family’s best interest; a primary coordinator can be chosen, and responsibilities must be understood across groups. Family members moving towards the coordination phase need to learn how to diffuse the intense emotional issues that bind families and, for their long-term welfare, develop healthy methods of communicating together.

Ming Lee took a leadership role in guiding her family to the coordination phase. She called together family members in anticipation of the potential sale of the family business. She reached out to her cousins and they developed a committee to receive input from family members, assess existing advisors, and develop the first meeting to start on the path to more effective family governance. This was quite fortuitous because within a year, two of the principals of the family business had died while the sale was going through. The family had a structure in place to focus on how to discuss common goals and develop a direction that led to the ultimate sale of the business and funding of a major new philanthropic entity aligned with the family’s principles and their community’s needs.

Are you in the Coordination Phase?

- You’ve had multiple family meetings, where numerous voices and perspectives were heard.

- Family members have worked collectively on articulating guiding principles.

- Your advisors work together cohesively and have a shared understanding of the family’s primary goals.

- Leaders of family forums such as a family assembly or council have been elected, appointed, or otherwise recognized.

- Family members understand the variety of roles they serve and can distinguish which matters belong where, understand who’s in charge of different decisions, and respect each role.

Phase Three: Cohesion. For families with multi-generational wealth, especially those that have created one or more philanthropic vehicles, reaching the cohesion phase is the final goal. Those in the cohesion phase have positioned themselves for continuity and succession of leadership, as well as engagement based on solid principles that are reinforced by effective policies and practices. An annual assembly might be used to bring together all family members and support relationships among them. Smaller groups will have been charged with leading collective efforts through a family council or other smaller governing body. The family will have developed policies for elections or appointments to these positions. Often, it will have created a sequence for elections to allow for smooth transitions and succession in key positions.

While some families might grant lifelong tenure, it may be wiser to establish term limits to increase inclusion and engagement. Family members in the Cohesion phase generally learn to separate emotional issues from the practical issues that must be managed and decided. They have learned to work as a team with their advisors. One or more family members might take the lead and serve as point persons for their generation or for the family as a whole. Most importantly, the family has sorted out when they must work together and when they can function separately.

The Riveras family reached Cohesion a generation ago, when they successfully transitioned to the fourth generation of their family philanthropy, business, and other collective work. They have successfully rotated through several leaders. Family members feel committed to their common principles, which are revisited every 5 years. They have had a family constitution for 20 years, and it has been amended twice upon vote of super majority of the family.

Has Your Family Reached Cohesion?

- You have consistent, well-attended, inclusive, and productive family meetings.

- You maintain different forums for different purposes, such as a family council and family assembly.

- Family members understand the family’s collectively agreed upon family principles—and know where to go to find them in documented form.

- There have been smooth transfers of leadership across various family entities.

- Power is dispersed rather than controlled by one or a small number of family members.

- Communication is open and healthy.

- Family related activities and decisions are transparent.

- There is accountability for following through on agreed-upon actions by family leaders.

Formal Informality

Family governance is not governance in its most formal sense. In family governance, most of what is decided upon is not directly legally enforceable. Rather, other documents and mechanisms create legal enforceability of certain aspects. Regardless, accountability must exist—both within the family and in recognition of societal concerns. For example:

- A family foundation’s bylaws will define the terms, eligibility, and limits for board members.

- State and federal laws governing the foundation will determine a board member’s fiduciary responsibilities. In law and practice, board members are accountable to society.

- A family assembly does not have comparable laws or expectations.

- A family council is generally an extra- legal entity that intersects with the legal governance in place, such as a board, and serves as a communication conduit for shareholders and other family stakeholders.

APPLYING THE FAMILY GOVERNANCE PYRAMID MODEL TO YOUR FAMILY’S PHILANTHROPY

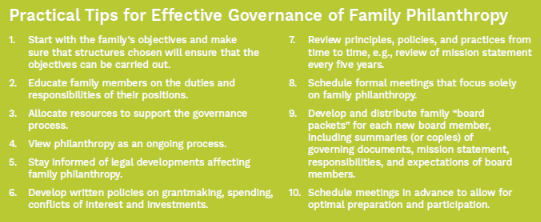

How can the Family Governance Pyramid help your family in its philanthropy? Basically, the same framework and process applied to family governance can and should be applied to family philanthropy. As you consider your family’s philanthropy (or a family philanthropy that you manage or run), there are some key questions that can help you assess whether alignment exists and what might be missing.

The family’s values and overall mission can be used as guideposts for its charitable giving programs. Further, the principles for its family philanthropy should guide the structures that are created and the way in which they are used.

Principles

In developing their overall family principles, families must devote time and energy to understanding and articulating what “comes first” and is enduring. They must also focus on clarifying the overarching values and principles that will be reflected in their philanthropic giving programs. Families should agree on a vision statement or otherwise articulate an overarching set of principles that provides focus for its philanthropic programs. With (or without) guidance from skilled facilitators in the philanthropic sector, families can develop a mission that is comparable to the others that have reached the cohesion stage. Doing so allows the family to keep the focus on the philanthropy itself, rather than on other aspects of the family’s interrelated affairs.

Questions to review around principles include:

- Has your family articulated the principles that it holds in common?

- What process did you use to develop your family’s principles? Was it inclusive?

- Are the family principles aligned with the family’s philanthropic work?

- Have you asked: What is the family’s highest calling—as a family, as citizens, as community members, and as philanthropists?

- Are the family’s principles useful as guides for your family? Can they lead you to higher aspirations?

- Have you considered your family’s role in society? What’s your understanding of the “social contract”?

- Have you addressed the difference been principles and values?

- Have you discussed how often you will re-visit principles?

- What might guide you in determining your principles?

- What questions haven’t you asked? Why haven’t they been asked?

An example of Family Philanthropy Principles

The David Rockefeller Fund provides a clear example of the power of Guiding Principles. The foundation’s website clearly states for grantees and the community what guides its work: In its work, the Fund seeks to address the root causes of problems, working both locally and on a broader policy level. Our efforts are guided by the following principles: Family Legacy, Risk Taking, Leverage, Respect, Flexibility, Self-examination.

Policies

Families with ongoing giving programs, whether formalized in a family foundation or not, should consider whether written policies would be helpful to guide the process of their giving. Even in informal giving, it is helpful to define how decisions are to be made and the respective responsibilities of each family member involved. At a minimum, there should be a conflict-of-interest policy, investment policy and a spending (including grantmaking, fees and expenses) policy. A policy with guidelines on the due diligence needed before a grant will be made can be helpful to keep all family members on a level playing field with respect to their differing charitable interests. For example, each family member should be required to support a grant recommendation with sufficient background information to enable the others to understand the merits of the grant and its recipient. Other policies might include:

- Board and Board Chair Position Descriptions

- Board Election, Classification, Term Limits, and Rotation Policies

- Board Eligibility Criteria and Guidelines for Board Membership

- Board Self-evaluation and Self-assessment

- CEO and Staff Performance Review and Assessment

- Code of Conduct

- Committee Charters: Executive, Nominating, Finance and Investment, Governance, Grants, Audit, etc.

- Discretionary Grants

- Diversity and Inclusiveness Statements

- Ethics Codes

- Expense Reimbursement Policies

- Matching Grants Programs

Questions to review around policies include:

- Is there alignment between your philanthropy policies and the family principles?

- Have you cross-checked your policies across other family endeavors?

- Do your giving policies align with your family principles?

- Are there areas that are not aligned? What can be changed?

- Have philanthropic policies been applied consistently? If not, why not?

Practices

The family should develop a practice of having formal meetings devoted solely to philanthropy. Records should be kept even if there is no formal structure. These will help guide the family along a path of increasingly effective giving. At the beginning, the family might focus primarily on its mission and vision for giving. Over time, outside experts from specific issue areas, such as arts, education, or economic development, could be invited to educate the family. Site visits should become regular practice. Family members can learn from one or more of the many associations and organizations supporting professional grantmakers.

In the Lee family, the oldest members have established a donor advised fund at their local community foundation. Four times per year, all generations convene by conference call to discuss the mission for their giving, share input that they have received from past grantees and assessments of current needs. At the last meeting each year, they decide upon specific grant recommendations for the year. Each family member is given the ability to make individual recommendations and group decisions are made by majority vote.

Families must stay on top of administrative requirements that could result in liability if not handled properly, such as tax filings and proper record-keeping. Families may find it useful to appoint specific family members, working in consultation with outside advisors where necessary, as the point person for issues such as investments, grantmaking, and governance.

Questions to review around practices include:

- Does your family apply its principles in its philanthropic practices? For example, how do you manage the power differential? If diversity is valued, how does that play out in hiring, grantmaking, investing?

- If you’ve practiced impact investing in a foundation, does that align with the family’s overall principles? Are there other areas that could use analysis to align?

- Does your family foundation have regular board meetings?

- Is communication between the family foundation and the public clear and consistent?

- Do grantees have a good understanding of the guiding principles behind your giving?

- Is process aligned with intent?

FURTHER THOUGHTS

Since the Family Governance Pyramid was first introduced, much has changed in the world—wealth inequality has grown exponentially, governance is under greater attack, and the concept of family governance has developed further. What lessons have been learned? Here are a few:

• Tradition prevails far longer than anyone realizes; families must identify what holds them back.

• Younger generations expect more voice/vote; families must heed their call to be heard.

• Theory is not enough; families need practice instituting governance.

• Entities are not enough; families must go beyond merely setting up forums.

• Families often excel in one area—governance of business, or family, or philanthropy, but need to connect governance across all endeavors.

• Governance needs leaders with certain qualities—listening, diplomacy, intuition, respect for rules, objectivity, focus on the whole.

• Anxiety, or desire for excellence, can hold back good governance instincts and processes.

• Outsiders can guide but can’t lead the family’s governance.

Thomas Jefferson stated, “It is not by the consolidation or concentration of powers, but by their distribution that good government is effected.” These words are as applicable to family governance as they were to the establishment of the governance of the United States. As we head into the future, it will behoove families to heed the words of the architect of the US governmental system in designing and implementing their own systems. Not only within the family but also in relationship with their partners in the community, and the larger society that depends even more than ever on their contribution to the social contract.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Corporate Governance Principles, Policies, and Practices, R. I. Tricker

Demystifying Decision Making in Family Philanthropy, National Center for Family Philanthropy

Family Governance A Primer for Philanthropic Families, National Center for Family Philanthropy

Family Governance Meets Family Dynamics: Strategies for Successful Joint Philanthropy, National Center for Family Philanthropy

Family Wealth Keeping it In the Family, James Hughes

Generations of Giving, Kelin Gersick

Inspired Philanthropy Your Step-by-Step Guide to Creating a Giving Plan and Leaving a Legacy, Tracy Gary

Robert’s Rules of Order, Henry M. Robert III et. al

Splendid Legacy 2 Creating and Re-Creating Your Family Foundation, National Center for Family Philanthropy

Succeeding Generations Realizing the Dream of Families in Business, Ivan Lansberg