Ten Facts Every Trust Beneficiary Should Know

By Patricia M. Angus – Originally published in Private Wealth Management in 2003.

After years of working with families to establish trusts, and with individual trust beneficiaries, it has become clear to me that there is a need for better understanding by the persons creating trusts and, more importantly, by beneficiaries, about what a trust is, and how trusts work.

Ironically, the beneficiary, who is the very person for whom a trust is established, is often quite confused about fundamental trust concepts.

In my view, the education of family members, especially beneficiaries, is as important as the creation of legal structures and the proper investment of assets to ensure the preservation and growth of family wealth and enhance the beneficiary’s life.

Further, legal and financial advisors, as well as trustees, should assist beneficiaries in the educational process.

This article summarizes some fundamental issues that advisors can and should strive to teach their clients.

The process should begin when a trust is created and continue for its duration. This will help the beneficiary better understand the trust and how the beneficiary can play an active role in its administration.

Obviously, this list hardly begins to address the complex set of issues that each trust entails. Hopefully though it can guide advisors as they raise their awareness and assist beneficiaries in the process.

1) Terms of the trust agreement

A beneficiary should receive a copy of the trust agreement, or at least relevant parts of it, from the trustee.

The trust agreement provides a set of instructions for the trustee and guidelines for the beneficiary.

The trustee should also provide a summary (oral or written) of the trust and be available to answer questions about its terms. It is only by reference to the specific provisions of the beneficiary’s own trust that the beneficiary will fully understand how they apply to him or her.

Key parties

The trust agreement defines the key parties to the trust relationship:

- the “grantor” or “settlor” contributes funds to the trust and generally sets its terms;

- the “trustee” is the individual, bank or trust company who is responsible for holding the trust funds and implementing its terms;

- the “beneficiary” is a person who is to receive current benefits (income and/or principal) from the trust;

- the “remainderperson” is anyone who is entitled to receive trust property when it terminates.

The beneficiary should seek clarification on what the trustee can or must do with trust income and principal.

Often, the agreement states that the trustee is to pay income to a particular beneficiary. This is generally annually or more frequently. It may also provide that principal is to be paid at certain ages or from time to time in the trustee’s discretion.

A trustee who has discretion over payment of trust income and/or principal is subject to certain standards that determine when payments can be made:

- under a broad standard, the trustee may pay principal for any reason, or not at all;

- a more restrictive standard might state that principal may be paid for the emergency needs of the beneficiary.

The beneficiary and trustee should discuss openly the types of payments that can be made.

Trustee’s powers

The trust agreement provides specific guidance on the trustee’s powers. This part contains important information that will give the beneficiary key ideas on what the trustee can and can’t do for him or her. For example, before the beneficiary calls the trustee to request a distribution, it would be useful to find out whether a loan would be possible. For tax or other reasons, it might be better for the beneficiary to take a loan rather than a distribution.

Beneficiary’s powers

The beneficiary should also find out what specific powers are reserved to the beneficiary. He or she may have a “ power of appointment”, which gives the ability to determine where trust property goes upon the beneficiary’s death.

2) Identity of the trustee, other beneficiaries, investment advisors, accountants and other advisors to the trust

The beneficiary should know who the other parties to the trust relationship are, currently and in the future.

The trustee can be one or more individuals or institutions.

There may be an investment advisor who is responsible for managing trust assets.

The beneficiary may be one of several people (family members or others) to whom income and principal may be paid. The beneficiary should understand whether, and to what extent, he or she has the ability to request or demand removal of the trustee. It is also helpful to find out whether there is a trust “protector” or other trust advisor.

3) Purpose of the trust

Ideally (but infrequently), the trust agreement contains a statement of the grantor’s reasons for establishing the trust. If the trust agreement is not clear , the beneficiary should seek clarification of the purpose. Understanding the mission will help the beneficiary keep the entire arrangement in perspective.

If the trust agreement is not clear, the beneficiary should ask the trustee, lawyer or other advisors for some background information. The beneficiary will not necessarily be happy with the grantor’s purpose. However, knowing the reasons may help keep potential frustration and anger in the right direction, rather than at the trustee, who is merely carrying out the grantor’s wishes.

4) Trustee’s duties

A trustee is a fiduciary and, as such, must act in the best interests of the beneficiaries and remainderpersons.

If a trustee takes advantage of its legal ownership of the property it faces not only the ire and wrath of disgruntled beneficiaries, but can also face legal action by them.

In addition, a trustee has a number of specific duties, including duties to:

- exercise reasonable care, skill and caution;

- keep and render accounts of administration;

- take and keep control of trust property;

- keep the trust property separate;

- make the trust property productive.

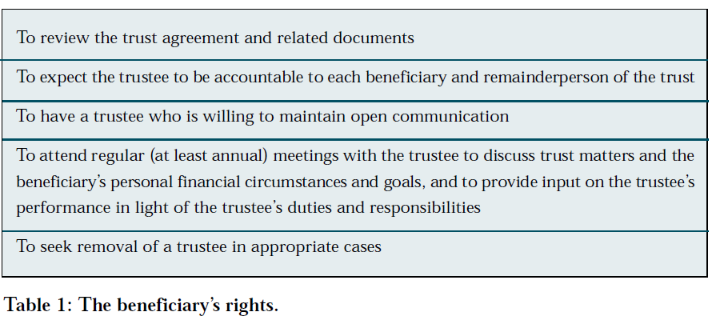

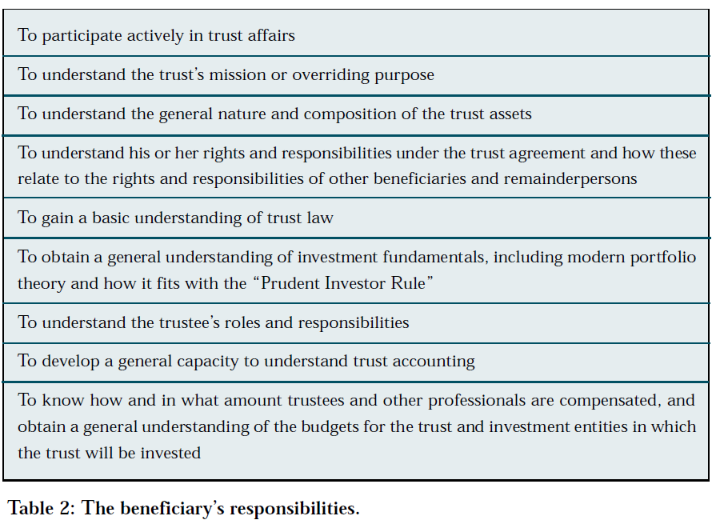

5) Beneficiary’s rights and responsibilities

One unique aspect of the trust structure is that the beneficiary is an integral, and indeed the most important, person in the overall structure. Yet often the beneficiary is not involved in the process of establishing the trust or in its administration. This can lead to an unhealthy feeling of dependence.

To maximize the benefits the beneficiary may receive from the trust and to ensure the wellbeing of the overall trust arrangement, the beneficiary should be comfortable with his or her rights and responsibilities (Tables 1 and 2).

6) Duration of the trust

Most trusts are governed by a local “perpetuities period”, which usually states that no trust (other than a charitable trust) may last more than one lifetime (starting at the time the trust is created) plus an additional 21 years. This centuries-old restriction is now being loosened in many jurisdictions. All new trusts in Delaware, South Dakota, Alaska and many other states (and countries) may now last in perpetuity.

7) General overview of trust accounting

A beneficiary does not need to become an accountant to gain a basic understanding of trust accounting. The basic concept – that a trust is established with contributed assets, known as trust “principal”, and any amount that is generated by that principal (such as interest or rent) is considered to be “income” – is quite simple.

More specific definitions of income and principal are provided by the law governing the trust. Indeed, the definition of “income” can be quite complicated.

The beneficiary should be aware that trust accounting principles are not always the same as tax rules. In this way, a beneficiary may be subject to tax on income that he or she did not actually receive but is attributed to the beneficiary.

8) General overview of trust law

Each trust is governed by the laws of a particular state (or country). These local laws and court interpretations provide guidance to the trustee and beneficiary about trust administration. In general, the terms of the trust agreement will apply to the extent that they are not otherwise prohibited by law. A grantor may choose the laws of a particular state or country, so long as there is a sufficient connection with that state to obtain certain benefits. For example, an increasing number of trusts are being established in Delaware because there is no state fiduciary income tax, asset protection is enhanced and a trust can last forever.

9) General overview of investment fundamentals

The trustee (or in an increasing number of cases, its delegate) will be responsible for investing trust assets.

The beneficiary should, at a minimum, understand the basic available investment options, including cash, stock, bonds, mutual funds, real estate, art and “alternative” investments such as hedge funds.

The trustee is responsible for deciding whether to retain the original assets and for ensuring that the investments match the trust’s goals.

The beneficiary should seek to understand the basics of “ modern portfolio theory”, which states that the most important factor in determining a port- folio’s performance is the allocation of assets over time – not stock picking or market timing.

The beneficiary should be able to engage in a discussion of each asset class, the historical return for each class and its function in the portfolio.

The asset allocation can and should be adjusted as the needs of the beneficiary – and the financial climate – change over time.

10) The “Prudent Investor” Rule

Traditional rules have limited the trustee’s ability to invest trust assets under a fairly restrictive standard that emphasize maintaining principal even if growth is hindered.

Under the new “Prudent Investor Rule” adopted by many states, a trustee must develop an overall strategy for the trust portfolio in the light of the present and future needs of the beneficiaries while taking into account risk and return. Diversification among asset classes is considered essential. The “total return” of the trust is paramount.

Each asset or class is looked at in the context of the entire portfolio. Trustees must balance income and growth. They may also delegate their investment responsibility so long as the delegation is prudent.

This law is being complemented by another new law to ensure that investments chosen for total return (including “growth” stocks) do not adversely affect income beneficiaries. New rules now allow trustees to adjust between income and principal and in some cases to choose a specific percentage (“unitrust amount”) of the trust to be considered “income” for distribution.

“Advisors should strive to teach their clients fundamental issues to help beneficiaries better understand what a trust is, how it works and how they can play an active role in its administration”

Summary

Many of the ideas in this article (especially beneficiary roles and responsibilities) have been explored in greater detail by James E Hughes Jr, who shares my views.

I hope that this article will add to the resources that advisors and beneficiaries can draw upon to reduce misunderstandings that can lead to conflict and to ensure that trusts are truly beneficial in the lives of their beneficiaries.

By helping a beneficiary understand the essential vocabulary and concepts of the trust relationship, an advisor can help increase the chances that the beneficiary will be equipped to work better with his or her advisors and truly benefit from the trust.