Guidance for Family Offices: How to approach ESG investing

By Patricia Angus and Camille Korschun – Originally published in Family Enterprise Insights, March 2021

Introduction: Environmental, Social, and Governance investing (ESG investing) is an approach that incorporates factors beyond financial return in an investment decision. Namely, the investor incorporates a broad range of criteria such as the business’s environmental impact, social practices, and governance to assess selection and performance. ESG investing is not a new concept and is the latest iteration of investing that incorporates qualitative as well as quantitative metrics. In the past, family offices have often been reluctant to incorporate this approach into their investments due to a lack of agreement about its merits both in families and the investment community. There have been conflicting reports on its efficacy in public markets and there is a paucity of data on its use in private markets. Nonetheless, demand at family offices for ESG investing is growing fast. Investment professionals in family offices must respond to this reality, and fast. With this in mind, this Family Enterprise Insights article provides guidance to family office investment professionals who are exploring ESG investment approaches in private and public markets for their family clients.

Introduction

For quite some time, investment professionals in family offices and those directly serving ultra-high-net worth (UHNW) families have been asked by clients to incorporate ESG investing across their investment mandates. In recent years, evolving social and political ideals have placed greater emphasis on the need for more environmentally and socially conscious investment strategies. The rising popularity of ESG investing, particularly among millennials, has resulted in widespread adoption of ESG investing and a proliferation of related products in the public financial markets. Though ESG investing has received much interest in these markets, its effect on quantifiable financial returns re- mains inconclusive. This, along with limited research and overall opacity about investments in private markets, have complicated the decision-making process investors face when contemplating incorporating ESG investing into their portfolios; however, over- whelming data from public markets indicates that it is worth serious consideration. Further, client demand is significant and will continue to grow.

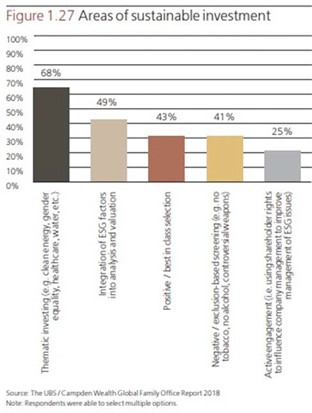

UBS’s 2018 Global Family Office Report found that thirty-eight percent of the firm’s family office clients were involved in sustainable investing.i Even among those families that had not yet adopted an ESG-oriented investment strategy, the majority indicated strong interest in incorporating more socially and environmentally-conscious investment strategies in the future. Today, the question is no longer if or why ESG investing should be included in a family’s investments but, rather, how.

Demand for ESG investing is often driven by younger family members, especially millennials, and is expected to continue to rise. At the same time, traditional resistance from older family members is loosening and there is now greater interest across generations. This raises some important questions: How should the family office help families navigate the ESG discussion within the family? How will they quantify their financial and societal returns? How will they ensure that their family’s core values are aligned with their investments? While many of these questions rest in the hands of the family and their advisors, as a practical matter it will be up to Chief Investment Officers, and those in equivalent positions, to address what these questions, and their answers, mean for family portfolios.

State of Play

Impact investing, ESG, and socially responsible investing (SRI) have become hot financial buzzwords. 2020 marked a historic year for inflows into ESG-focused funds, the culmination of an increasing shift toward sustainable investing over the last several years. Institutional and retail investors alike have shown increasing interest in investing in these funds. In 2019, ESG funds saw $21.4 billion in inflows. In 2020, that number grew by more than 100 percent, with Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) enjoying the greatest growth.ii One such example, IShares ESG Aware MSCI USA (ESGU), the largest ESG ETF, witnessed an astounding eightfold in- crease in total assets, from $1.5 billion in 2019 to $13 billion in 2020. As a result of the considerable rise in popularity of funds like these, everyone from fund managers to academics seems to have turned their attention toward ESG investing, which, in turn, has lit a fire under research efforts that had long overlooked this area.

Recent research confirms value creation in companies that monitor their environmental footprint, social interaction with communities, and governance practices. A 2013 study that investigated companies’ disclosure of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and their access to financing concluded that companies with high CSR performance had lower capital constraints.iii This lower barrier to accessing capital markets resulted in greater stakeholder engagement and, as such, a long- term approach toward profitability.

A similar study published by Harvard Business School found that there were lower capital constraints in firms with superior social responsibility, and that greater CSR disclosure resulted in superior stakeholder engagement with a view toward long-term profitability value creation.iv The growing adoption among public fund managers has resulted in overwhelming amounts of ESG data cover- age by sell-side analysts and the adoption is justified. A study conducted by Eccles, Ionnou, and Serafeim (Harvard Business Re- view, 2011) analyzed both high and low sustainability companies over an 18-year period. They found that the high sustainability companies outperformed those with low sustain- ability in terms of both stock market and ac- counting measures. Additionally, a greater focus on sustainability was found to be associated with long-term oriented investors.v Though this early evidence may be compel- ling, there is still much work to be done, especially in determining appropriate definitions of the terms used (for example, ESG and SRI are terms that are used to mean a variety of investment approaches). Indeed, un- til recently, the adoption of ESG investing had been slow due to skepticism among tra- ditional investors of the approach itself which partly reflects the lack of clarity and agreed- upon benchmarks. Critics of ESG investing are quick to point to inconsistencies regard- ing how financial and social impact metrics are quantified and monitored, both within in- dividual holdings and as part of a diverse portfolio. For example, iShares ESG Aware MSCI USA ETF (ESGU) is, on the surface, an ESG- focused ETF. However, a deeper dive reveals that industry-leading oil and gas companies are among its core holdings. Investment professionals face lack of transparency as they conduct due diligence and make decisions about more sustainably focused investment endeavors. As the primary liaison between the family and family’s portfolio, it is imperative that family office investment professionals conduct appropriate ESG-focused due diligence prior to bringing a potential in- vestment to the family. The advisor must learn more about the array of investment choices and the spectrum of approaches to gaining financial returns with societal benefit.

Beyond the Public Markets

Families should not view this new endeavor as all-or-nothing – it is rarely a good idea for a family office to go “all in” on one investment approach and ESG investing is no exception. Indeed, this area provides a learning opportunity; one that will enable multiple generations of a family to learn about ESG investing and allow members to work collaboratively around a common strategy. Ultimately, a family can use the process to help them learn about their shared values and beliefs and how to translate these values and beliefs into action within the family’s portfolio. Given the inconsistency of definitions and confusion among available investments, responsible ESG investing simply requires an- other layer of due diligence. This will also en- sure alignment with the family’s core values. Family office investors are in a position to provide this important guidance.

While family office investors can find a plethora of ESG data for public markets, ESG research is still nebulous in the private markets. Lack of rigorous data is among the greatest difficulties family offices face as they endeavor to steer the ESG discussion, though the tide is beginning to shift. UBS projects that the ‘social good’ investing trend will continue to grow with future genera- tions.vi A notable thirty-nine percent of respondents reported that, once the next generation assumes control of their family offices, they will likely continue to increase investment allocations toward impact investing. After 2020’s record-setting year, the move toward ESG inclusion is widespread. Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum, communicated his support for ESG in- vesting when he stated, “Performance must be measured not only on the return to share- holders, but also on how it achieves its environmental, social and good governance objectives.”vii

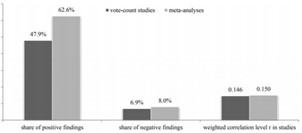

Recent studies indicate that corporate financial performance (CFP) and ESG metrics are not necessarily mutually exclusive. In 2015, researchers extracted data from 2,200 separate empirical studies and found that 90% of the studies had a nonnegative ESG-CFP relation.viii

Of these, 62.6% of the meta-analyses found a positive correlation between ESG and CFP. This remains the most comprehensive study of ESG investing to date. A dataset of this magnitude could easily be extrapolated to private markets, as well. Yet, despite data from the public markets that clearly indicate financial viability, institutional and private investors often believe that the relationship between ESG and CFP is neutral at best.

Private Equity’s Skin in the Game

Though many studies have indicated that there exists a positive correlation between ESG and CFP, scholars still vacillate on how significant an impact a company’s or fund’s ESG practices has on its return profile. Nonetheless, private equity firms have invested tremendous time and resources to raising funds with the sole purpose of investing in high social and environmental impact companies. Leading firms, such as TPG Capital and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR), have doubled down on their commitments to ESG. At the beginning of 2020, TPG was nearing its target of $2.5 billion for its Rise Fund II; and, more recently, KKR closed $1.3 billion for their Global Impact Fund, which will invest in lower middle-market businesses delivering solutions to societal challenges. This ESG pledge by private equity firms signals a shift in this space to commit capital toward businesses that provide more than financial returns. It also provides further evidence that ESG has become an essential component of a diversified portfolio.

Incorporating ESG into family portfolios

Given this context, ESG will soon likely be a fundamental part of nearly every family’s portfolio. Demographic trends will only accelerate the process, as family offices shift to serving millennials as their primary client base. Families are now compelled to find their core values and consider their legacy more seriously as a result of this shift toward ESG investing. Family office investment professionals will need to be sure that the family can be skillfully guided to have conversations around topics including specifying allocation amounts, differentiating the family’s impact investing from their philanthropy, and setting financial expectations. Establishing tangible guidelines will help solidify how the family will successfully integrate ESG while retaining family cohesion.

There is no “one size fits all” approach that will apply to all family offices. Each family has unique needs and highly personalized investment strategies and missions, and their goals for ESG investing may vary widely. For instance, one family may find a common interest in climate change and be highly motivated to seek ESG investments that are aligned with carbon neutrality, whereas an- other family may be more interested in gen- der equality. Families will need to work together to identify their aligned values and objectives when it comes to ESG investing.

Family offices must also help their family clients add new metrics beyond financial returns to their investment policy statements. The investment due diligence process may need to include factors such as environmental impact, employment generation or diversity reporting. This may present a challenge to family offices with well-established investment processes, especially purely quantitative ones. In addition, family office investors may need to need to help families navigate difficult conversations and facilitate decision-making by individuals, trustees, and other groups of investors. This involvement will include determining where the family is aligned in its values, focusing on the similarities across generations, and then determining whether ESG investing is appropriate in a specific account.

Once a family determines they would like to incorporate ESG factors, and identifies the impact they would like to achieve, the family office investor must ensure proper implementation. The work necessary for such implementation will likely be gradual, so that it al- lows family members to learn and adapt to a new way of investing.

Suggestions for Implementation

Of course, most families have portfolios that cannot, and should not, be changed overnight. And it is unlikely that all family members will have 100% agreement on their investment goals and preferred outcomes. Each account must be viewed as a separate portfolio and should have its own investment policy statement. The family office investment advisor and account owner (family member, trustee, etc.) will need to follow a process that reviews goals, risk tolerance, and liquidity needs, among other traditional factors, to develop an appropriate investment portfolio. Integration of ESG should be considered for each account separately. If pursued, the investment advisor will need to know how aggressively to pursue that strategy. The traditional starting place for ESG investing has been to apply “filtering.” For example, a family might identify climate change as a cause they hope to impact through their investments, which consequently causes them to identify fossil fuel and tobacco as unacceptable industries in which to invest. Their investment advisor would then divest any holdings that may directly or indirectly benefit companies that operate in these sectors. This traditional approach may help families become more comfortable as the family office develops its capacities and adopt external sources for ESG data. As next step, the family office could adopt the more current approach of applying an ESG lens more holistically. This might include actively sourcing deals within the environmental vertical (for example, a manager might look for opportunities within the renewable energy sector). Segmenting each of the ESG factors and helping the family think of each individually (environmental, social, and governance) may help families in the long run.

Peer networking can also benefit families when navigating the ESG investing discussion. Many family enterprises have been at the forefront of ESG integration, and with their assistance, they have educated other families in the early stages of exploring ESG investing. This positive peer-to-peer interaction has helped families become more comfortable with adopting new approaches and practices. Family members might attend academic conferences and join networking groups to explore not just ESG investing but the burgeoning world of values-based family practices and investing.

Conclusion

With its growing popularity, as well as a multitude of new resources to help guide families toward successful integration, ESG investing is here to stay. While families must decide for themselves whether ESG, or another aspect of impactful investing, is right for them, family office investors will play an integral role in guiding them through the process of deciding if, when and how they would like to integrate ESG investing into their existing investment strategies. Ultimately, family office investment advisors will be critical to successful ESG integration. Not only will they need to navigate the complexities of ESG investing, but they will also need to guide families through the collective decision-making processes that will lead to a successful and rewarding investment strategy. In this way, the family office will help direct not just the family’s financial capital but also help shape the family’s legacy.

Patricia M. Angus Esq. is an adjunct professor and Managing Director of the Columbia Business School Global Family Enterprise Program. She is the CEO and founder of Angus Advisory Group LLC.

Camille Korschun is Senior Associate Director of the Columbia Business School Global Family Enterprise Program.

The authors wish to acknowledge research assistance from Lance Alan Jubel, Columbia College ’20.

i Rep. Global Family Office Report 2018. UBS, n.d.

iii Dhaliwal, Dan S., Oliver Zhen Li, Albert Tsang, and Yong George Yang. “Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting.” Accounting Review 86, no. 1 (October 5, 2011).

iv Cheng, Beiting, Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Access to Finance.” Strategic Management Journal. May 25, 2011.

v Eccles, Robert G., Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim. “The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance.” Management Science 60, no. 11 (February 2014).

vi Rep. Global Family Office Report 2018. UBS, n.d.

vii Schwab, Klaus. “Davos Manifesto 2020: The Universal Purpose of a Company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution.” World Economic Forum. December 2, 2019.

viii Gunnar Friede, Timo Busch & Alexander Bassen (2015). “ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment. 5:4, 210-233.