Governance for Business-Owning Families (Part II): It starts at the top

By Patricia M. Angus – Originally published in WealthManagement.com March 2018

The world is full of family businesses. Literally. Most of the world’s businesses are owned, controlled and often managed by a group of family members.1 These families face challenges that are quite complex, including how to do well in the business and in the family, too. The news is replete with stories of family feuds that spilled over into the business and vice versa. Is this how it has to be? Well, based on the experiences of business-owning families who are thriving, the answer is no. What are these families doing differently? This article is the second in a two-part series looking at how good governance can help families who own businesses and who want to do it well for the family and the business. This just might be the difference between the stories you don’t hear about (often the better ones) versus the ones that make up the headlines.

Our Entrepreneurial Couple

Part I of this series in the March 2017 issue recognized the reality that most families overlook the challenge of “governing” all that they do together inside, and outside, of the business.2 These families already have governance in place, whether they’ve acknowledged it or not. In Part I, the reader followed George and Martha, an entrepreneurial couple, who were quite successful in developing a commercial product that increased the efficiency of farm operations. Over time, they set up limited liability companies (LLCs), trusts and related structures to organize their operations and minimize taxes and liability. They were thoughtful about the future and did some estate planning. Shares of the business were transferred into trust for their children and future generations. At the same time, their family grew, and their children, Betsy and Abe, joined them in the business. Readers learned how this couple unwittingly created a range of governance bodies and made recommendations for their advisors to help them and clients like them. Well, that was all some time ago. Let’s now pick up the story of George and Martha’s family some time later.

Catching Up With the Family

Thanks to their excellent advisors, George and Martha followed some of the advice from Part I and created governing boards for each of their businesses, even including independent members to add outside expertise and perspectives. They set up formal trust meetings, and the trustees and beneficiaries are all actively engaged in understanding how their trusts can work best. The original business has expanded, and there are now several spin-offs in addition to the original one. Also, the family has been able to take some of the profits out of their businesses and has started a growing investment portfolio through another LLC. They’ve even started talking about doing some philanthropy together.

Even though there’s so much positive activity in their lives, things aren’t always easy for the family. George and Martha are getting on in age and really want to step back from day-to-day work, which seems reasonable as they both see age 75 not far on the horizon. Over the years, the family has grown, and some tensions have arisen from time to time. Where there were just two parents and two siblings, now there are inlaws, ex-inlaws, children and stepchildren. Abe has been married twice and has two children from his first marriage. His new wife has several children of her own. Betsy was widowed young and has since remarried a man with three children. George and Martha just love being with all their grandchildren and consider them all equals. The age range is quite wide, however, and the cousins don’t all know each other. Abe and Betsy will both reach age 50 soon, but their spouses are older and younger than they are, respectively, by some years. As a three generation, blended family, things have become a little complicated. At times, the business seems to be the easiest thing the family does together. What are they to do?

Well, now’s the time for the family to think beyond business and family and focus on another kind of governance—that is, family governance. Even in a family that’s relatively small and gets along generally well, there’s still a need for family governance. As in comparable families, there are just too many people, too many ideas and too many levels of legal authority and responsibility spread throughout the family that they can’t ignore it any longer. Actually, when one of the cousins stormed out of the last family Thanksgiving gathering, it reflected the animosity that had been growing among several members over quite some time. Sadly, the family’s fortune seemed to be at risk of dissipating through family disharmony. No one is quite sure what the future holds.

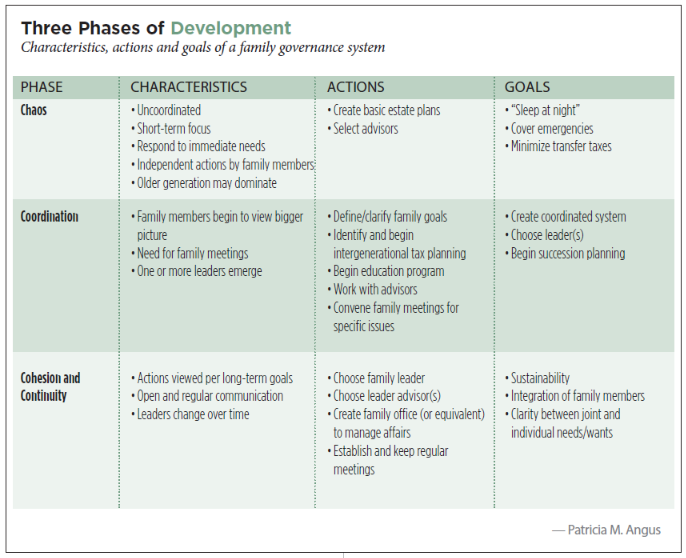

George went to a lawyer friend to talk about it. Martha confided in friends. Abe asked his college roommate what to do about it. And, Betsy found a consultant who specialized in family governance. The family didn’t know that such consultants existed, and there was much hesitation among the group, but they were open to suggestions. Here’s what they found out and the path they’re now forging.3 (See “Three Phases of Development,” p. 45.)

Starting Point: Chaos

Even though George and Martha have done excellent estate planning, and they have good relationships with their children and grandchildren, they’re actually in the first stage of family governance: Chaos. That is, there’s little alignment or integration of all the planning they’ve done, and it isn’t wholly in sync with the way the family functions together. If something happens to one of them, the rest of the family wouldn’t necessarily know what to do. Imagine that George had a stroke. He’s been the primary leader of the planning, the CEO of the company and the only one who speaks to the lawyers and accountants on a regular basis. Further, he’s the chair of the board of the holding company that owns all the family’s businesses. As in many families, the others (including the “independent” directors) tend to defer to George on major decisions. This has worked well for a long time, but—in side conversations at family gatherings—there’s often a shared concern about what happens if “something happens” to George. The unspo- ken thought is that “something happens” means some- thing quite disturbing for all. Due to their love of him, they find it hard to bear the thought of his not being a part of their lives. For that reason they’re unwilling or unable to imagine a different way of doing things. Well, for that reason, and also the fact that they are afraid of offending him. He doesn’t take his own mortality too lightly, it turns out.

Imagine—just for now—the inevitable happens. And, in fact it, could happen to any member of this family at any time. Martha might predecease George, even one of the children might. Or, maybe not as inevi- table, but in some ways equally disruptive to the family, a buyer might come along with an offer that’s too good to refuse, and the family will have to decide whether to sell all or part of their business. What to do then?

Next Step: Coordination

Hopefully, long before one of these major family events ever happens, the family will decide that it’s time to get to the next phase of family governance: Coordination. Any family that shares businesses, family trusts, investments or philanthropy together must, at some point, start work on coordinating how these activities will be handled, as a family. Whether they like it or not. What does this mean? At a minimum, the family will need to have meetings to make sure that they all understand the roles and responsibilities that are already in place for them. In George and Martha’s case, they appointed their children as trustees of some long-term generation-skip- ping transfer trusts through their lawyers but somehow failed to mention it to either child. While the businesses have had a board of directors for a while, the family hasn’t given any guidance on what they really want out of the companies. Moreover, ownership is now dispersed across a series of trusts and individual shareholders, and they’ve never had a shareholders’ meeting. And, while the estate planning has been excellent, and their advisors are top-notch, most family members have no relation- ship with them and have little knowledge of the details in theory or practice.

Most importantly, like so many families, financial returns aren’t all that they want to get out of the business—they also care about their identity, reputation, role in the community and commitment to all stakeholders. To them, success includes what’s known as “socio-emotional” wealth, something that’s hard to define, but they know it when they see it.4 As a practical matter, it would help to coordinate the work of their lawyers, accountants and financial and investment advisors. Not just to optimize their returns in the short run, but also to set up some back-up plans and common knowledge before it’s needed. At this stage, it’s often helpful to start having “advisors’ summits.” At least once a year, the entire team gets together to assess the overall picture. Ideally, each advisor contributes a perspective on what’s going well and what could be improved so that there’s an ongoing planning dialogue at the family level. Within the family, it’s time to start dividing up responsibilities. For George and Martha, they might realize that Betsy has the greatest interest and acumen for investing. She could take the lead on working with the investment advisor. Abe might prefer to think about the family’s role in the community. He might take the lead on some joint charitable giving that the family wants to do together. The family, with their advisors, and on their own, could start some vision exercises to articulate where they want to be in five, 10, even 50 years and discuss their common values. The key to this work is to focus on the “heart” of the family—that indescribable way that families are connected. Families who explore their relationships, communication pat- terns, expectations and common purpose can achieve far more than those who haven’t done so. In this area, it’s likely they’ll need to add a new advisor to the team: a consultant who can help facilitate this discussion. For some families, this will be a new member of the team; others might feel comfortable working with someone from one of the existing firms in the mix.

Cohesion and Continuity

If all goes well, and the family has weathered the inevita- ble events, sometimes crises, that befall them along the way, they can look forward to reaching the third stage: Cohesion and Continuity. This is the stage at which the family knows what holds them together and what doesn’t. They’ve come to terms with what they want to do together and what they don’t. And, there’s an edu- cated group of family members who respect each other with tolerance and understanding. Even if it’s not all “kumbaya,” they function as a healthy group.

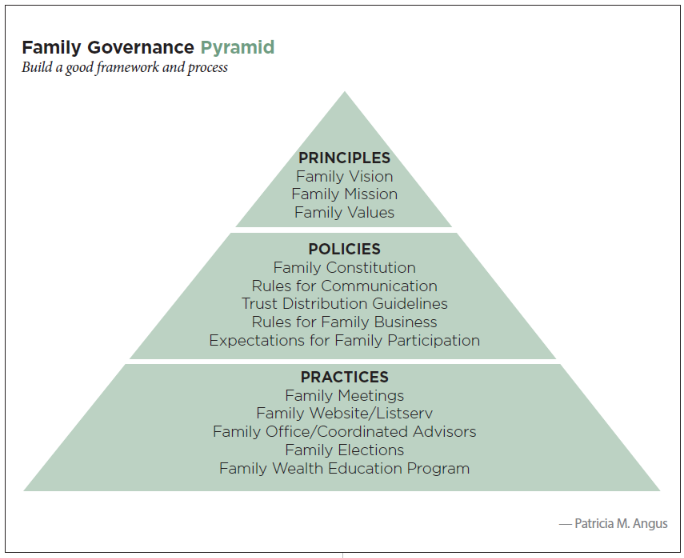

For George and Martha’s family, this might lead to having annual meetings of all family members, some- times called a “Family Assembly.” The Family Assembly would be used to focus on the common values, vision and mission that define the family’s guiding principles. By coming to common agreement on these principles, it becomes much easier to do the follow-up work of setting relevant policies and making sure their practices are aligned with the principles. Governing can be an intimidating word and seem quite ephemeral or archaic. But, having a framework and process that works for the particular family can make it seem quite natural.

At the annual meeting, it’s always good to have some time to get to know each other outside the business and outside the family. Just to relate to each other as individuals pursuing their own paths aside from the family enterprise. Many families find this enlightening and a chance to support each other in new ways. They could also set aside time for the shareholders to have their meeting(s) and for reports on investments, philanthropy and any other family endeavors. Each separate meeting would only include the family members who are appropriate for the specific meeting. And, perhaps most importantly, there would be some genuine fun time for the family together. This helps foster healthy relationships among the cousins, who may someday own the business (or make important decisions together including whether to sell the business). Of course, not all family members will be close with each other, and they might not even like each other but—if they’re going to co-own anything together as a family—they need to establish some authentic relationships, and family governance will assist in this process. (See “Family Governance Pyramid”).

Reality Check

This all might sound too good to be true. Are families really capable of governing themselves? Should they? Well, the answer is yes. First, because they’re already doing it. Whether they realize it or not, families already have a way of governing themselves. There are psycho- logical ways of making decisions that are ingrained in the family. And, for the lawyers in the group, it’s obvious that they already have governance responsibilities— corporate boards, owners, trustees, beneficiaries and co-owned assets. The question is whether they want to be intentional—and successful—at it, or not. The business-owning families who have taken the approach outlined in this article who are thriving can attest the power of combining framework and process.

Endnotes

- See www.ffi.org/page/globaldatapoints.

- See Patricia M. Angus, “Governance for Business-Owning Families: Part I,” Trusts & Estates (March 2017), at p. 57.

- See also, Patricia M. Angus, “Family Governance Pyramid: From Principles to Practice,” Journal of Wealth Management (Summer 2005), at p. 7.

- See, e.g., Pascual Berrone, Cristina Cruz and Luis R. Gomez-Mejia, “Socio- emotional Wealth in Family Firms: Theoretical Dimensions, Assessment Ap- proaches, and Agenda for Future Research,” Family Business Review (2012), at p. 258.