Family Governance: A Primer for Philanthropic Families

By Patricia M. Angus – Originally published on NCFP Passages in 2004.

Families who engage in philanthropy together have a unique opportunity to make a positive impact on the world and to share an experience that can enrich their lives beyond measure. At the same time, many families find that managing the work that must be accomplished as a group can be as complex as the grantmaking itself. By its nature, family philanthropy draws upon the passions, knowledge, and skills of many family members.

Families seeking to optimize the potential of their philanthropic experience may find that an understanding of the overall meaning of family governance can help them manage the process. Family governance is a relatively new concept, and has been applied less to philanthropy than to business and other areas.This Article aims to help philanthropic families understand some of the theory and practice of family governance, and how effective governance can help them in this work.

WHAT IS FAMILY GOVERNANCE?

As a conceptual theory, family governance is still in the early stages of development, with more being learned every day. In recent decades, practitioners and academics from various disciplines have been developing a theory and practice of family governance as a way to assist families with long-term wealth preservation and growth. James E. Hughes, Jr. provides an extensive overview of the family governance concept in his book, Family Wealth: Keeping it in the Family. In Family Wealth, Hughes makes a compelling case that families who seek to preserve wealth across generations must expand their focus beyond financial capital by also supporting the family’s human, intellectual, and social capital. Under this theory, philanthropy represents a crucial element of the family’s assets, as it reflects the social capital of the family. A family invests its social capital by means of its public works and community contributions, including philanthropy.

Family governance concerns itself in part with the management of the complex web of relationships that develop among family members, most notably when there is inter-generational wealth. Typically, a family’s philanthropy, whether formal or less structured, is only one of a number of ways in which family members interact with one another. In addition to the fundamental connections among family members, there are often family trusts, companies, foundations and other entities that create joint ownership and joint interests involving members of the family. These entities, and the relationships created by them, can seem overwhelming to families without the practical guidance that family governance can provide.

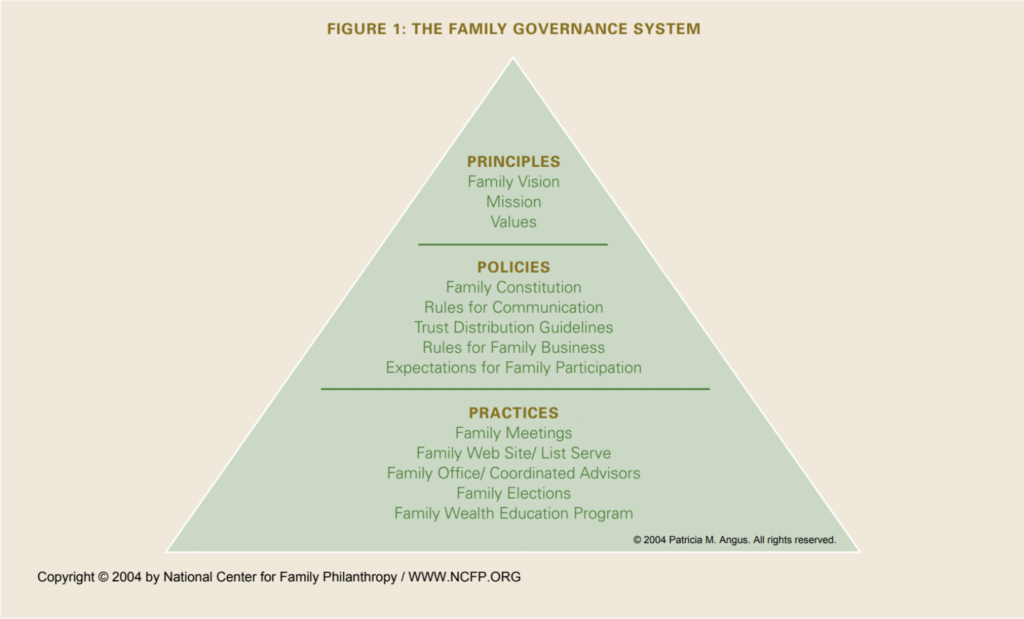

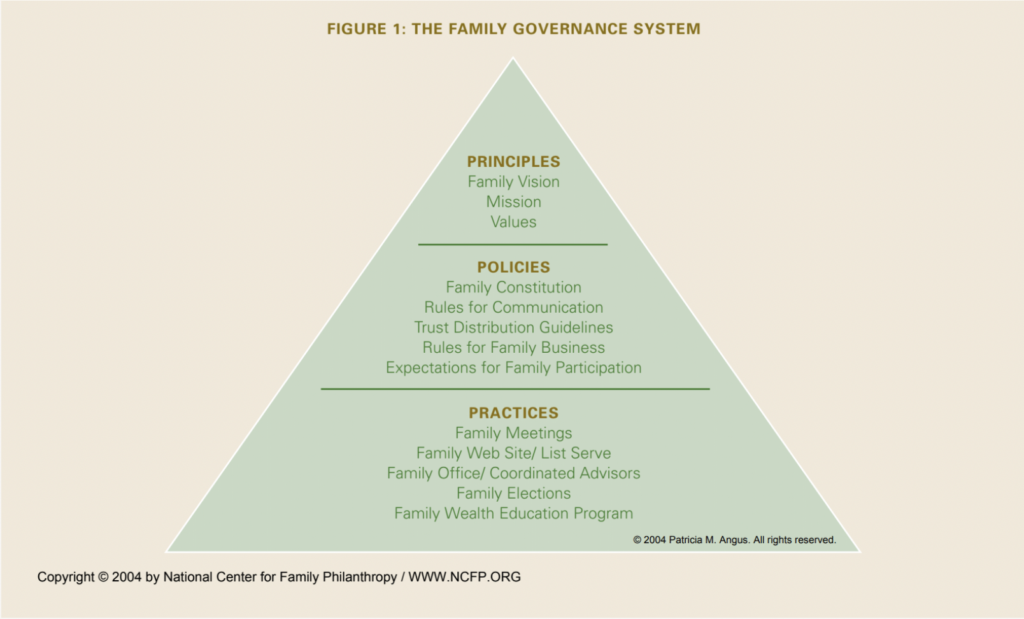

While there are many approaches, this article focuses on some crucial elements of family governance: principles, practices, and policies developed and implemented by the family in a supportive environment. This article also provides observations on the usual stages of the governance system and suggestions for its potential applications to philanthropic families.

DEFINING “FAMILY”

In family governance, the definition of family is broader than a group of persons related solely by blood or marriage. It includes other important members who are joined to the family by an important relationship with one or more members.1 This acknowledges that families no longer fit the stereotypical nuclear model. For example, divorce may divide the traditional family tree, and many families now expand their tree to include couples, same sex or otherwise, that are a part of the family but do not fit in the traditional slots. Close friends may develop relationships that are as intricate, and intimate, as family. In some wealthy families, there are also professional advisors and staff who are treated as family, both financially and emotionally.

GOVERNING THE FAMILY

The ways that governance traditionally functions, for example at the local or national level, are paralleled to a certain degree in families. This is particularly true for those who have created legal vehicles such as private foundations and family trusts. A basic dictionary definition defines governance as “the act, process or power of governing; the state of being governed” while to govern means “to control the actions or behavior of; guide; direct. To make and administer public policy for…exercise sovereign authority in….” While only certain (i.e., royal) families rise to the level of sovereignty, this definition gives a sense of family governance. It may be uncomfortable to think of family members guiding, directing and controlling one another’s behavior, but as result of their legal, tax and charitable planning, this is often a potential result. This is because each structure creates new legal rights and responsibilities for family members.

“Most families of significant wealth are already living within family governance systems, whether or not defined as such.”

Jack H. Friedenthal, former Dean of George Washington University Law School, observed that law consists of regulating human behavior through language. How laws are written affects human behavior in a variety of ways. Laws set parameters for acceptable behavior (e.g., the legal drinking age) and, in more subtle ways, they affect behavior by providing consequences for specific actions. Similarly, when family members write wills, trusts and other legal documents, they set out governing rules that affect their own family members, often for generations to come.2 These documents place certain family members into positions of authority (e.g., as trustees or directors of family foundations) that not only subject these family members to specific laws and regulations governing their behavior, but also change their status within the family. For example, an uncle may become trustee of his nephew’s trust. Depending on the terms of the trust, the uncle may have the power to withhold or make distributions of income and/or principal to the nephew. Obviously, the relationship between the uncle and nephew will be affected by this legal reality.

Most families of significant wealth are already living within family governance systems, whether or not defined as such. Virtually all wealthy families have established structures to minimize taxes and order their affairs. They have created wills, trusts, family limited partnerships and similar vehicles that create roles and responsibilities, and that grant authority to certain family members that can affect others. While the goals for these structures are often limited to minimizing taxes, or, perhaps, providing for minor children, the actual consequences may go far beyond the original intentions. For example, a family with $5 million is likely to create a credit shelter trust to ensure that each parent’s estate tax exemption amount (currently $1.5 million) passes through two generations free of estate tax. While intending to save taxes, parents using this strategy have made their children into trust beneficiaries rather than outright inheritors. This in turn has very different consequences for their children, and for the parent’s relationship with their children. A child who inherits funds outright will be solely responsible for investing and spending those funds. By contrast, as a trust beneficiary, he or she will generally not have legal control over investments nor unfettered access to the use of the funds.

Even when family members are appointed to positions of legal authority, they are often given little guidance about how to exercise that authority, or about the parameters in which they must function. For example, in the early stages of a family’s philanthropy, the eligible trustee candidates of a family foundation may be defined as “family members over the age of 18,” or as “all family members living in the community in which the foundation focuses its giving.” Unless the family pursues a trustee education program, a family member may become responsible for making distributions without deep understanding of philanthropy, and the laws and regulations that govern this important work.

EFFECTIVE FAMILY GOVERNANCE

What constitutes effective family governance? There is no single system that applies to all families. Nonetheless, observations of successful families reveal that the system must be based on an agreed upon set of principles, policies, and day-to-day practices that are followed by the family members who choose to be part of it. (See Figure 1.) The family must also maintain an environment that supports the governance system. The system must be flexible and open to all family members, who are given the choice to join or leave (or, in some cases, to defer their involvement). It must be adaptable to the inevitable changes that will occur within the family and the world in which they live.

PRINCIPLES

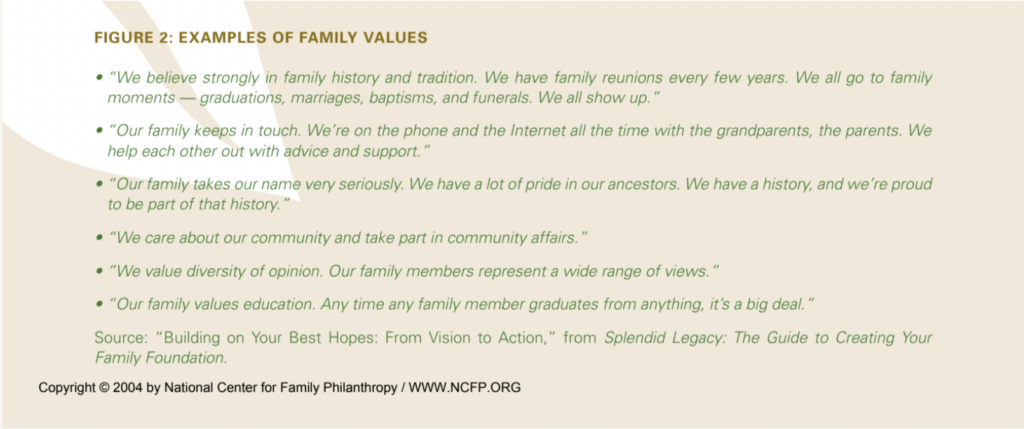

Nothing truly extraordinary happens without an overriding vision or set of unifying beliefs. This universal truth applies to family governance. In Succeeding Generations, Ivan Lansberg asserts that a family must pursue its “shared dream,” which transcends the dream of any single family member.3 A family must work together to discover its own vision, values, and goals. The family must consider:

- What are our shared beliefs?

- What distinguishes us from other families?

- What vision do we hold in common?

Families might choose to develop a mission statement, vision statement, or list of shared values. Family members cannot assume that everyone will agree to each value or aspiration; rather they must respect the differences among themselves while focusing on the overlapping values that hold them together. (See Figure 2.) One way that principles can be found is through an organic process that is both aspirational (How do we wish the family to be seen?) and practical (What is an example of our family’s uniqueness?).

The Tyler family developed principles for governance in a series of family meetings.Their first two meetings focused on getting a handle on the family’s trusts and financial situation. By the third meeting, the family had a sense of the magnitude of their wealth and how it would be managed across generations. But the family did not yet see itself as a team and did not yet see how its financial structures would affect important activities of the family, including the shared family philanthropy.

Under the guidance of an outside consultant, the Tylers stepped back from the financial details and spent an afternoon sharing ideas about how they viewed, and wanted the world to view, their family. The consultant facilitated a process in which each family member was given an equal amount of time to tell a story about the family and to describe the ways in which he/she felt that the family was unique.There was much laughter and even tears. As the consultant began to weave the stories together with the family, family members realized that they collectively valued independence and self-sufficiency as a highest priority. They remembered the fierce independence of their ancestor who had left Europe alone and made his fortune in the United States.

At the end of the process, the family’s values and goals were well defined, and, as a result, they were able to articulate a family mission: to promote the self-sufficiency of current and future family members as they pursue their own talents and development, and to help others who are “making it on their own” despite difficult circumstances. As a focus for their philanthropy, they created a scholarship program for inner city students who had excelled academically but would not otherwise be able to attend college.

POLICIES

Families must establish ground rules for interactions about shared matters. While some families find it useful to establish a family constitution, others find that guidelines for family meetings are all that is needed. Policies should be written or, if not, must be simple enough that all family members can remember and agree to them.

The Cooke family agreed to have an annual meeting, called the “family assembly,” to discuss issues of common concern. All family members over age 15 are invited to attend but only those over age 18 can vote. The assembly lasts two or three days, and covers the family business, finances, philanthropy, and other issues. The Cookes agree that spouses can attend some of the sessions, but they are not invited to specific financial and trust discussions. The family schedules separate activities for spouses while those discussions take place.

PRACTICES

Family members must follow an agreed upon governance system in their day-to-day interactions. To do so, it is important that they develop a set of accepted practices that support their principles and policies. If there is a family office, they need to staff and support it properly. The family should consider what methods of communication work best. Some families decide to establish a secure website and/or list serve. There may be separate sections for different areas such as trusts, foundations, and financial resources. Some family websites have secure sections so family members can access information about their own trusts and investment accounts. The charitable section of the website might include minutes from past meetings of the family foundation and a record of grant-making spanning the time period since the foundation was formed. It can also include links to the websites of some of the organizations funded by the family.

The Cooke family regularly schedules “family check-in” time at each family assembly. Each member of the assembly shares information about his or her family, work, and important life developments. One area covered is an update on the family members’ charitable learning process and giving experiences. This is a way for the family members to learn more about each other and provides an opportunity to gain some leverage from individual learning efforts.

PROPER ENVIRONMENT

Experts agree that families must foster an environment with the following characteristics for governance to be successful:

Open communication. The lines of communication must be open, both among family members and between the family and their advisors.The family must strive to overcome the challenge of communication across distances.

Respect for the uniqueness of each family member. The family must understand that members of different generations—and even the same generation—will view the world and their lives very differently.

Sense of community. As a corollary to respecting each individual, there must be a sense of community among family members for their joint endeavors to succeed. Focusing on commonly held goals can help foster community within the family.

Clear distinction between group and individual needs/wants. Individuals and groups both need to be accommodated. For example, it is inevitable that members of different generations, and even those from the same generation, will have very different views of how foundation funds should be disbursed. In anticipation of this, families should create guiding rules to minimize the potential conflicts that might arise. For example, allowing discretionary grants or dividing the foundation’s funds into separate groups—by mission or otherwise—might be more appropriate than seeking unanimity on all decisions.4

Respect for rules. The media has been increasingly focusing on families who have used their businesses and charitable funds for their own purposes. It is essential that families educate those serving as trustees on the wide variety of rules governing private foundations and other legal entities. Equally important, families must ensure that the actions of family members follow these requirements. In addition, the family must attempt to adhere to the rules that they’ve established for themselves. For example, if a family foundation has established a grant evaluation and approval process, it should be careful before letting individual members of the family make grants that do not follow the process.

PHASES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF A FAMILY GOVERNANCE SYSTEM

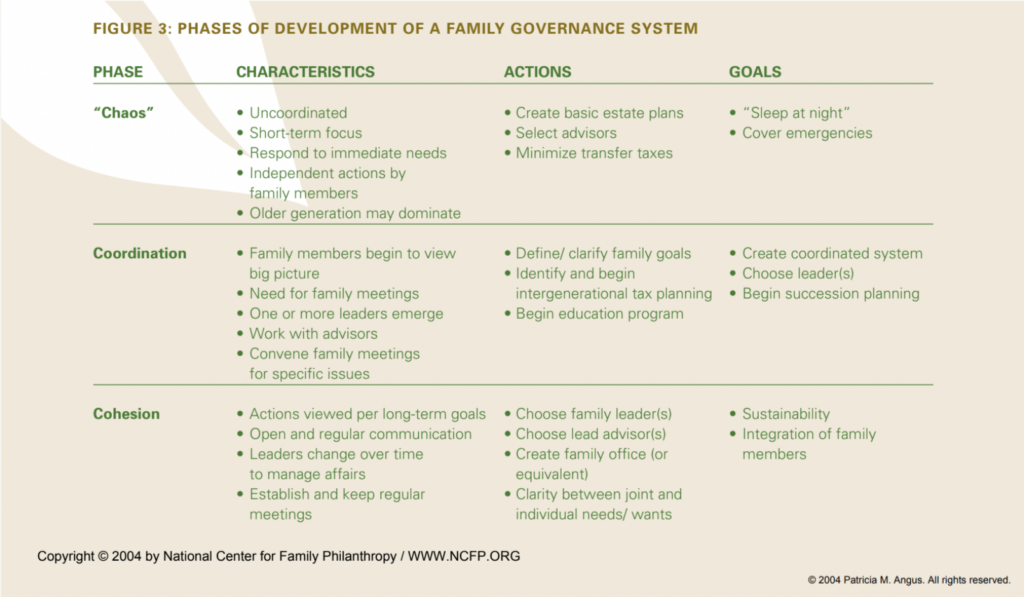

There are three basic phases in the development of a family governance system: chaos, coordination, and cohesion. Figure 3 on the following page summarizes the typical characteristics, actions, and goals of each of the three phases in the family governance system.

Phase One: Chaos. In science, chaos theory describes situations that from the outside appear to be the result of random or unpredictable acts, but in reality have an underlying order that can be discerned over time. While there is by definition an element of disorder in chaos, this theory has shown that merely observing the “disorder” of a given situation is helpful. For the majority of families, “chaos” may describe their situation with respect to family governance. This does not mean that the lives of the family members are in chaos! Rather, family members are focused on living their lives and, along the way, set up structures to meet specific needs as they arise. For very good reasons, they are more focused on day-to-day issues than long-term wealth planning.

For example, young couples often write wills after their first child is born or before they take their first family vacation. Many entrepreneurs establish and fund a private foundation as part of the sale of a business, even though they may not have time to do long-term planning. In many cases such as these, family members do not focus on administration and long-term goals. Stability usually depends more on the underlying dynamics and relationships of family members than the role of their advisors and the structures created by the family. Usually a family’s patriarch or matriarch overshadows the rest of the family during this stage. Family members aren’t necessarily unhappy about this, but often the facade of stability belies underlying chaos.

The Jones family has been very comfortable with the fact that the patriarch, Samuel, who has been tremendously successful in his manufacturing business, handles all of the family’s estate planning. However, Samuel is now 80 years old and in failing health, and has never discussed the details of how his assets are held with his wife or two daughters, now in their 40’s. His family is currently unprepared to take on the investing, charitable giving, and other responsibilities they could inherit at any time.

Phase Two: Coordination. As a result of a crisis or other significant event, such as a death in the family or sale of the family business, many families find it necessary to coordinate their affairs in one or more ways. Sometimes, a family member or group will take initiative and create a more formal way of working together. This usually involves an initial family meeting or a series of meetings, starting with specific issues that need immediate resolution. This is a crucial phase, as it presents an opportunity to work on core governing principles and policies. Ideally, it is during this phase that a cohesive team of advisors is formed, a primary coordinator is chosen, and responsibilities are understood across groups. Family members need to learn how to diffuse the intense emotional issues that bind families and, for their long-term welfare, develop healthy methods of communicating together.

After their mother’s funeral, the Ingalls family found that they needed to set up monthly conference calls for the three surviving children. These calls helped members of the family to begin to understand the existing trust structure, to hire investment managers, and to manage the charitable foundation set up in Mrs. Ingalls’ will.

Phase Three: Cohesion. A minority of families reach the final phase, cohesion. In this phase, the family develops and applies an integrated system for handling its commonly held assets and intertwined affairs. Family members generally learn to separate emotional issues from the practical issues that must be managed and decided. They learn to work as a team with their advisors. One or more family members might take the lead and serve as point person for their generation or for the family as a whole. Most importantly, the family is able to sort out when they must work together and when it is appropriate to function separately.

The Wall family has been working together for nearly 10 years since the oldest member and family patriarch, Fredrick Wall, decided to initiate family meetings for his successors. They now have a family constitution that has been agreed upon by members of the two oldest generations (ranging in age from 90 to 25). It contains a family mission statement and set of by-laws that provide rules for inclusion in the family council, working in the family business, and involvement in the family foundation, among other issues.

The family council meets once a year, just before the family business shareholders meeting and annual foundation meeting. The family council appoints a member to the board of the family business. The family council reports to the family assembly each year. Administration of all family matters other than the family business has been transferred to the family office.

FAMILY GOVERNANCE AS A GUIDE FOR FAMILY PHILANTHROPY

While family philanthropy might appear to be a discrete aspect of a family’s affairs, in many ways it represents the epitome of the need—and potential—for family governance. As the media increasingly focuses on private foundations, stories are surfacing about families who have overstepped the bounds of the law with their charitable foundations. In this environment, it is crucial that family members become educated about the roles, responsibilities, and authority that they have attained as a result of their family’s philanthropy. For example, it is very likely that family members will be considered “disqualified persons,” through relationship with the donor or as a result of making a donation to the family philanthropy. Legal counsel must carefully review their interactions with the family foundation. Similarly, as trustees, family members assume fiduciary responsibility and owe a set of duties to the foundation itself and will be held to one of the highest standards under the law.5

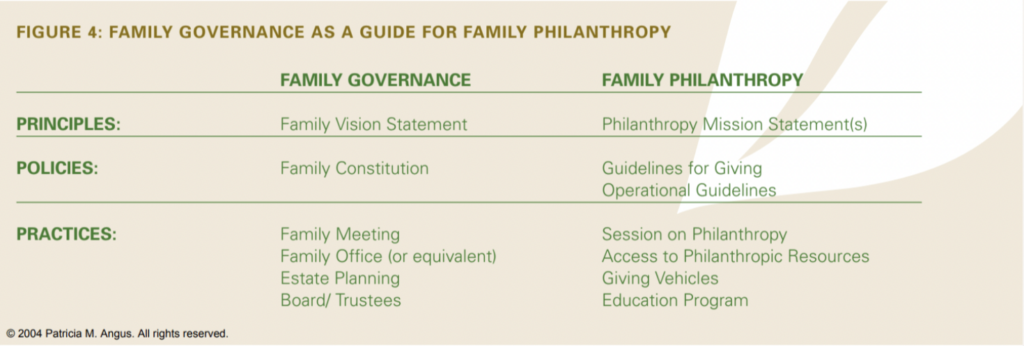

While liability issues are important, it is clear that applying proper governance to family philanthropy canmake the experience go more smoothly and be more rewarding. A family’s values and overall mission can be used to guide its charitable giving programs. Further, the principles for a family’s philanthropy should guide the structures that are created and the way in which they are used. Betsy Brill, President and Founder of Strategic Philanthropy Ltd., a philanthropic advisory firm, points out that structures are often established without a full understanding of the family’s philanthropic objectives. She states: “Almost every client who comes into my office hasn’t been asked the critical questions that—had they been asked by the initial advisor—would have led to the appropriate structure.” In one case, a family that had established a charitable trust found that it needed to be completely re-structured in order to accommodate the way in which they wanted to incorporate the voices of the community as a part of the decision-making process. Some specific ways that family governance can guide family philanthropy are introduced below, and outlined in Figure 4 above.

“The principles for a family’s philanthropy should guide the structures that are created and the way in which they are used.”

PRINCIPLES, POLICIES, AND PRACTICES FOR EFFECTIVE FAMILY PHILANTHROPY

As noted above, in developing their overall family governance principles, a family must devote time and energy to understanding and articulating what the family stands for. Similarly, they need to focus on the overarching values and principles that are reflected in their philanthropic giving programs. The family should agree on a vision statement or should otherwise articulate an overarching set of principles that provides focus for their philanthropic programs. Guidance from experienced professionals can help a family develop a mission that explains their overall goals and ties them to societal needs. Engaging in such a process will help the family to keep the focus on the philanthropy itself, rather than on other aspects of the family’s inter-related affairs.

Families with ongoing giving programs, whether formalized in a family foundation or not, should also consider how written policies might help guide their giving process. Even in informal giving, it is helpful to define how decisions are made and the respective responsibilities of each family member involved. At a minimum, there should be a conflict of interest policy, an investment policy, and a spending (including grantmaking, fees and expenses) policy. A policy with guidelines on the due diligence needed before a grant can be made will help keep all family members on a level playing field with respect to their differing charitable interests. For example, each family member should be required to support a grant recommendation with sufficient background information to enable the others to understand the merits of the grant and its recipient.

“Even in informal giving, it is helpful to define how decisions are made and the respective responsibilities of each family member involved.”

Finally, families should develop appropriate philanthropic practices, including formal meetings devoted solely to philanthropy. Records should be kept even if there is no formal structure. These will help guide the family along a path of increasingly effective giving. At the beginning, the family might focus primarily on its mission and vision for giving. Outside experts from specific issue areas, such as arts, education or economic development, may be invited to help educate family members, and provide feedback to their specific interests and ideas on current needs and existing programs. Site visits should become regular practice. Family members can learn from one or more of the many associations and organizations supporting professional grantmakers. (See the “Making Connections” section of the National Center for Family Philanthropy’s website, www.ncfp.org, for a comprehensive list of these organizations.)

In the Kim family, the oldest members have established a donor advised fund at their local community foundation. Four times per year, all generations convene by conference call to discuss the mission for their giving, share input that they’ve received from past grantees and assessments of current needs. At the last meeting each year, they decide upon specific grant recommendations for the next year. Each family member is given the ability to make individual recommendations and group decisions are made by majority vote.

Families must stay on top of administrative requirements that may result in liability if not handled properly, such as tax filings and proper record-keeping.The family may find it useful to appoint specific family members as point persons for issues such as investments, grant-making, and governance for their philanthropic programs.

Kathryn McCarthy, a long-time advisor to wealthy families on philanthropy and other issues, emphasizes that the family should keep the process fun, yet formal enough that family members understand the importance of their work. In one family, the older generation established a donor advised fund and sought input from younger generations. In the end, it seemed, the older generation may have learned the most from one 10 year-old member who provided an extensive proposal for a grant.The family videotaped her presentation, finding that the seriousness with which she approached the issues, combined with her youth, provided just the right tone for ensuring effective, rewarding philanthropy. McCarthy urges families to focus on the process rather than approaching philanthropy in a merely transactional way.

CONCLUSION

Families are often advised that family philanthropy will help keep them together and preserve wealth across generations. They are also encouraged to engage in family philanthropy so that they can experience how gratifying it can be. By gaining an understanding of the theory and practice of family governance, and adapting it as they see fit to their family philanthropy, a family may be able to achieve these goals and much more.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES ON FAMILY GOVERNANCE

- Esposito, Virginia, ed., Splendid Legacy: The Guide to Creating Your Family Foundation. Washington, DC: National Center for Family Philanthropy, 2002.

- Gersick, Kelin., John A. Davis, Marion McCollom Hampton, and Ivan Lansberg. Generation to Generation: Life Cycles of the Family Business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997.

- Gersick, Kelin, et. al., Generations of Giving: Leadership and Continuity in Family Foundations. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Publishers, Inc., 2004.

- Hopkins, Bruce R. The Law of Tax-Exempt Organizations, Eighth Edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003.

- Hughes, James E. Jr. and Patricia M. Angus, The Trustee As Regent in the Family Governance System. 1999.

- Hughes, James E., Jr. Family Wealth: Keeping It in the Family. Princeton, New Jersey: Bloomberg Press, 2004.

- Hull, Robert. The Trustee Notebook: An Orientation for Family Foundation Board Members. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Family Philanthropy, 1999.

- Lansberg, Ivan. Succeeding Generations: Realizing the Dream of Families in Business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1999.

- McCoy, Jerry J. and Kathryn Miree. Family Foundation Handbook. Frederick Maryland: Aspen Publishers, Inc. 2001.

- Rounds, Charles E., Jr. Loring: A Trustee’s Handbook. Frederick Maryland: Aspen Publishers, Inc. 2001.

- Senge, Peter M., The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York, New York: Currency Doubleday. 1990.

- Stone, Deanne, Grantmaking with a Compass: The Challenges of Geography. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Family Philanthropy, 1999.

ENDNOTES

- See Passages, Vol. 6.1, “Families in Flux: Guidelines for Participation in Your Family’s Philanthropy”

- Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary defines governance as “the act, process or power of governing; the state of being governed.” To govern means: “To control the actions or behavior of; guide; direct. To make and administer public policy for … exercise sovereign authority in …”.

- Ivan Lansberg, Succeeding Generations: Realizing the Dream of Families in Business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1999.

- See Passages, Vol. 3.2, “Discretionary Grants: Encouraging Participation… or Dividing Family?” and Grantmaking with a Compass: The Challenges of Geography.

- For more information on “disqualified persons” and other related issues, see “Facing Important Legal Issues,” in Splendid Legacy: The Guide to Creating Your Family Foundation.